A Letter from a Voyager

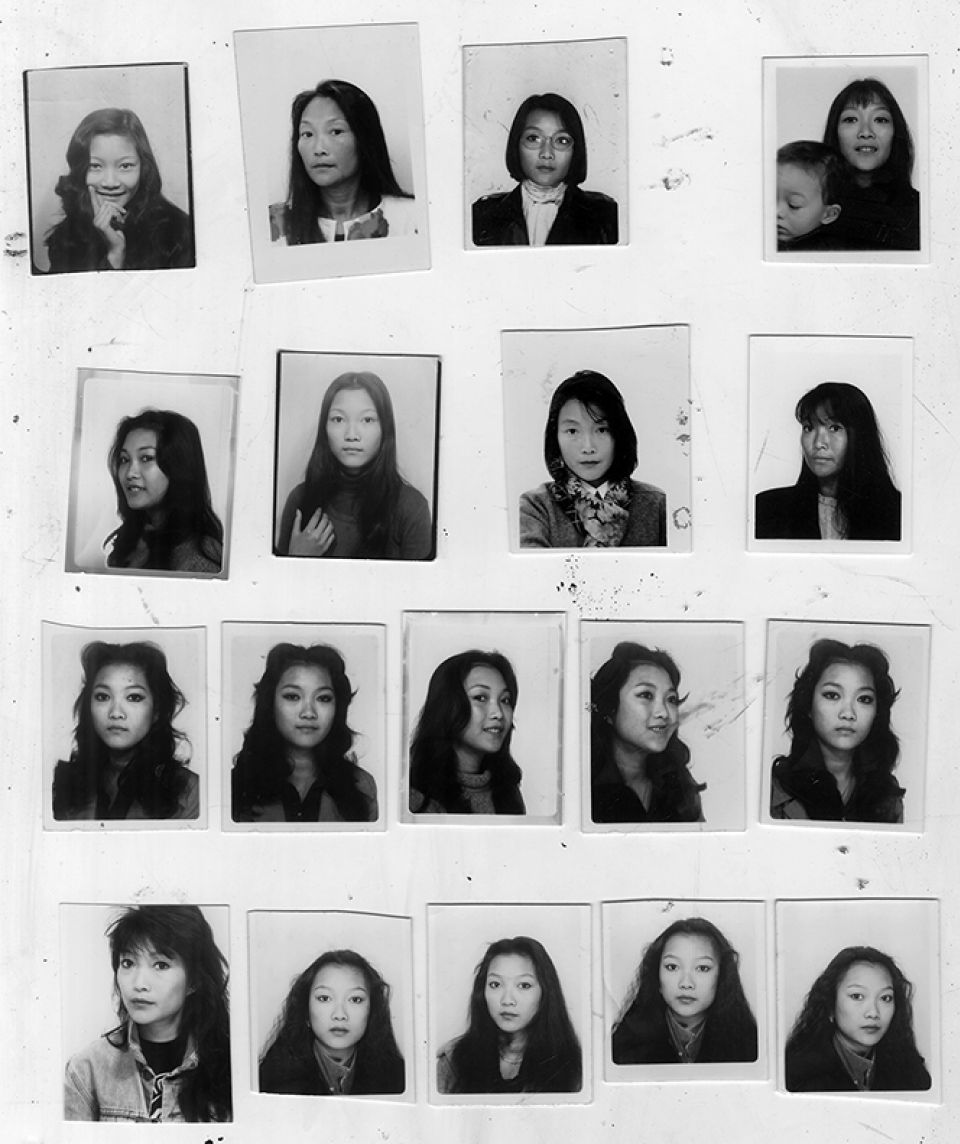

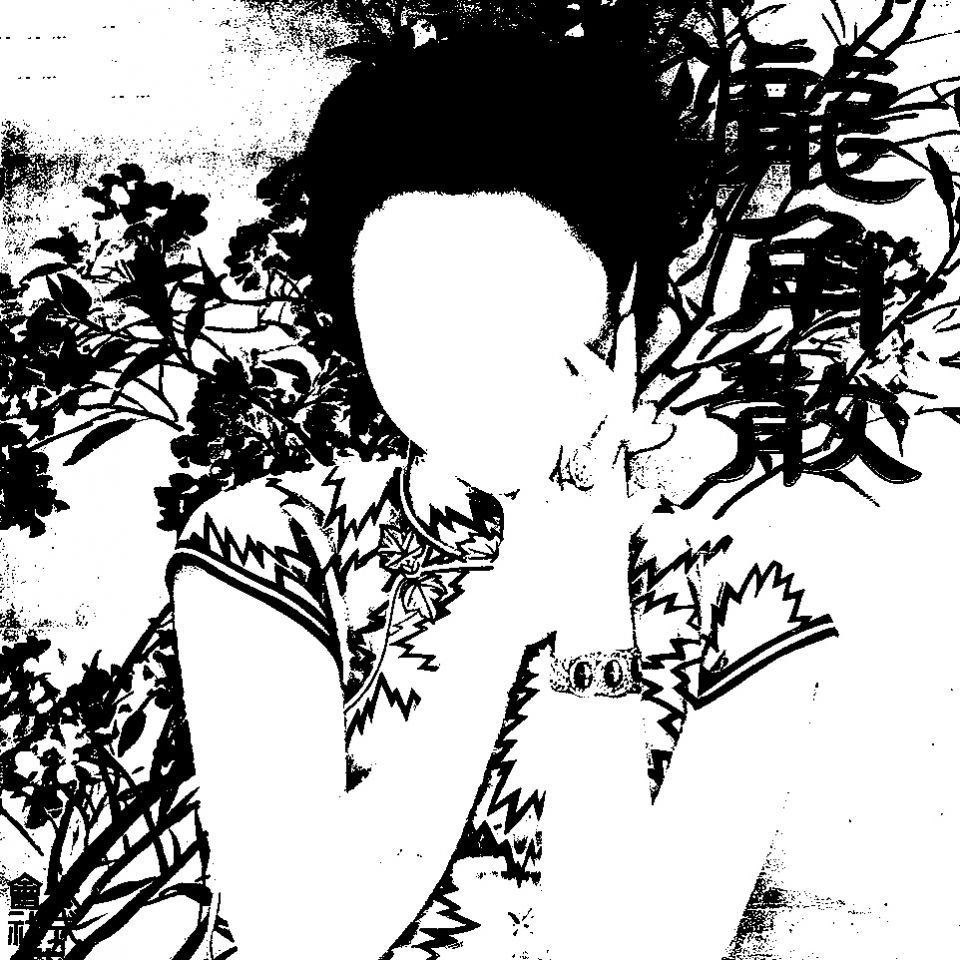

Illustration by Jiayue Li 李佳玥

When people in Paris ask me which part of China I come from, I answer that I was born in a city called Chengdu, in Sichuan province in the south west of China. Since it isn’t a notable name that rings as familiar as Shanghai or Beijing, I’ve always been surprised by the amount of interlocutors who knew about the place, including some who had already made a little expedition there.

If you pay a visit to Chengdu today you’ll count a population that now outnumbers 16 million; you'll be looking at a dispersed metropolis of concrete jungle, linked by broad avenues and winding flyovers. Each day you expect new skyscrapers to rise from the ground, luxury shopping streets to keep stretching on and on, and traffic jams to extend to the next crossroads. Modernity is far and wide: paying an elderly merchant with your phone at a flea market is officially commonplace; a multitude of apps are here to satisfy whatever your needs are—from booking a manicure appointment to ordering a large bouquet of blossoms. You see a city full of energy and business and opportunities, built up on dreams and desires and aspirations. Those who come from the country or small towns would like to make it there. Some start off as construction workers and ascend all the way up to become wealthy entrepreneurs; an almost official story of aspiration or success for many. Those already accomplished enjoy a life full of material comforts, with access to the best that fortune can offer. And this is a reflection of what most are longing for.

Merely 30 years ago, the backdrop of my childhood Chengdu would lead you seemingly to another epoch entirely. Needless to say, there were no signs of any form of extravagance. No traffic jams, as it was so rare for households to even possess a vehicle, a car being a real luxury at the time. Some of you may have heard that over the last decades cities in China have been involved in a cycle of tearing it all down to make way for the new; a new that is propped up on top of the ashes, full of ambitions and belief. Modernisation is the key word. Such acts have somehow erased the remainder of the bygone past, the last memories of a long-standing empire, with the exception of a few tourist sites. We’re heading to the age of a Brand New People’s Republic of China. We don’t have much to mourn, because the majority of the country’s antiquities were already taken during the Evasions. Ironically, the first time I was able to appreciate the extraordinary wealth of ancient Chinese heritage was in collections at the Louvre in Paris and the Metropolitan in New York, when I was already an adult. There has literally been a generation of Chinese who have grown up without much of their past, besides a few volumes of history and some fictionalized TV serials.

In the early 90’s Chengdu’s urban area was of a much smaller scale, and tightly circled by farmers’ fields—so close you could bike to the countryside in just an hour or so. My father used to take me to the brook in the summer; in the clear water we would swim against currents at our own risk, or fly kites on the dirt tracks near a railway, within these fringe urban-rural patches of the city. Back then, this was certainly not the picturesque region depicted in the present day videos of Chinese YouTuber Li Ziqi (who’s famous for her celebration of the bucolic and gastronomic delights of nearby Pingwu County in Sichuan, and is considered the Mainland’s most acclaimed YouTube personality). Yet even today, the footage of these quotidian pastoral scenes that document Li Ziqi’s exquisite savoir-faire in the arts of cuisine, crafts and cultivation—laced with a great deal of style and taste, appealing to both Eastern and Western audiences—remains an idyllic fantasy more than a general reality. Her compelling visual narratives have nevertheless altered people’s lingering perceptions of the residents of these once rustic and destitute lands. We have moved forward.

In my childhood we had barely begun to recover from the turbulent years of the Cultural Revolution, when China was stripped of its own history and disconnected from the rest of the world; sidelined from both our glorious past and from the West’s divergent ideology. There wasn’t much material to turn to about the outside—occasional old American movies on television, sometimes some news. Before the avalanche of TV series and films finally arrived from the West, mainly America, in the late ‘90s, the American show Growing Pains first came to Chinese screens. It illustrated the USA’s entirely different lifestyle, amusing and bemusing viewers: from American’s housing arrangements to their family dynamics and relations, from the fact they all had gardens and garages to their strange manners of communication. Everything seemed so distant from us, and in the end, so much better. No more than 30 years ago, life was nothing like it is today. International travel was reserved for the extremely privileged, government officials and the elites, or inversely for the most impoverished ones, who clandestinely escaped the hardships of their existence at home in the hope of pursuing a better life elsewhere.

We grew up lacking confidence in our national industries, products, education and so on, whilst all media projected the world outside China as if it were completely overwhelming. And those who had been out there confirmed such with their first-hand accounts. Xenophilic sentiments had begun to prevail at home for a while by then, with people admiring the West’s economic achievements and the material comforts that go along with it. Though only a handful of people could engage in a real conversation with the Westerners who traveled to China, English far from being a strength of our educations, it didn't hold us back from throwing curious glimpses at the outlanders in friendly interest, thinking how fascinating it was that we looked and talked nothing alike. There weren’t many of these Westerners strolling about a city like Chengdu, the only couple I knew were English teachers. The question of race was scarcely a subject, as there had barely been anyone other than us natives in place for generations. Nevertheless, we still all tacitly knew being ‘white’ entitled you a certain legitimacy. We all had heard lousy stories of Chinese citizens being treated poorly in the West; which could have just been urban myths, but that image embedded itself. This lies in ironic contrast to our present days, when I see Paris’ Michelin restaurants so eager to attract lavish Chinese customers, who are even more eager to relish French gastronomy and sign its fancy bills.

As I grew older, China ramped into full speed economic growth, which could be seen in our everyday life—the low old buildings were razed to be replaced by high rises, the lines of fields receded, highways extended yet still became ever more crowded. As the traits and features of the city evolved, so did those of their inhabitants.

Concurrent with the economic boom grew the fashion of traveling abroad—for leisure and in particular education. Sending a family’s only child to study overseas became both an important investment and a means of fulfilling a number of children’s once exotic dreams. I was part of that wave.

Paris, the city of light—lacking in neither references nor luminaries; embellished as much by the classics as by pop culture; wearing the dazzling spectacles created around her like jewels. It certainly isn't short of visitors, such as I first was upon my arrival to study, one more tourist-like individual, strolling the lengths of its narrow pavements. I hadn’t expected people to mirror back to me the curious glances we used to show foreigners in China, and most of the time I shied away from these intimidating gazes, that here seemed to signal rejection rather than intrigue. Before the arrival of waves of international students and tourists in the 2000s, in the local’s eyes the handful of us in town were mostly a diasporic population associated with all types of Chinatown commerce, until we later came to be seen as passionate long-haul shoppers (whilst at the same time easy prey for muggers). After years of receiving these looks in various settings, I seized that these gazes, willingly or otherwise, were products of a chain of stagnant stereotypes and partial portraits. I came across people who imagined China to be a nation guarded by a population of naturally skilled Kung-Fu fighters—the last time this was a cab driver, barely a friendly straight talker, he still left me giggling awkwardly as I tried to talk him out of this fantasy. Undoubtedly, we owe such a reputation to the notable universal powerhouse of cultural communication—Hollywood—which successfully implanted this notion in its international public. And they haven’t exactly come up with any sufficiently refreshing ideas over the years since. I once read a book by a Korean-American author, who talked about how we had expected that literature could bridge cultural divides, whereas in reality the publishing industry tended to lean on the ‘single story’ of ethnic writers, publishing and replicating ethnic patterns over and over again. And so it is in Hollywood, the same market-tested models endlessly repeated—if they are ‘authentic’ enough for the audience, why bother digging more, why change the story, or the character? But I have to say we’re entering a better time, now that major productions are taking initiatives to counter stereotypical models—beginning first with casting, and now with more international creatives coming into sight, the most notable recent evidence being Boon Jong-Ho’s wide acclaim. The immense success of Parasite has confirmed again that there’s so much more than a ‘single-story’, to be both produced and read.

A senior lady, whose only source of information about China had come through her television screen, once told me she knew that Chinese cities are filled with obese people, amongst many other mind-bogglingly marginal stories that pictured us horridly. So heartily I argued that only the most fractional truths had been shown in these programs, and that the newspeople on this continent were ill informed about Chinese culture, and basically irrelevant to the topic. Yet this seldom affected her. I concluded that she genuinely wanted to receive biased, verging on misleading, opinions, because she wished to focus on the otherness—that the West is opposed to the East—disregarding the much that we have in common, so that she may readily despise that which she would never try to understand. I reckon there are still those who rely on Marco Polo’s narratives as sources of facts.

But it would be untruthful to tell you that it was simply occasions like these that propelled me to conceive of Ying Xiang. It is clear that dealing with misunderstandings is inevitable, if our choice is to dwell on another’s ground. Frustrations were sometimes tapered by meeting people with extraordinary knowledge of my origins—whether from their own adventures or as the product of the savviness of a life-long passion—not to mention an expanding community of Westerners speaking fluent Mandarin. It is still almost surreal for me to carry on a conversation in this tonal language, far from China—unimaginable mere decades ago; after all, the French idiom ‘c'est du chinois’ is literally used to mean ‘things incomprehensible’. I’ve been pleasantly surprised over and over.

Yet recently I had a hard time hiding my disappointment upon becoming aware that one of my all time favorite broadcast media had been putting out phony stories on territories they don’t know, and don’t intend to know, just to bait their audience and satisfy a false sense of justice. I was a bit less surprised when the Trump administration set out China as the ultimate enemy of the West, placing the country in the sights of both the President and his MAGA supporters, to distract people from his failures and shamelessly create so much more hatred between communities, when tensions are already at such a critical level because of the current global situation.

And then there’s my experience of my career in fashion. Six years ago I went through a fashion exhibition that dealt roughly with the theme of ‘China’, together with one of the few Chinese designers that was being exhibited. Being totally bemused at seeing ‘China’ dealt with as meaning barely more than orientalism (even though the exhibition’s title had implied this quite plainly) I realized with great alarm the common position of international creatives. My everyday work in the fashion industry put me in the forefront. I observed how easily the West discredited, and dominated, the narratives and perceptions of creatives from other lands; how often culture was misinterpreted through a lack of awareness or information; and, increasingly, how often the term ‘diversity’ is peddled and touted, as nothing more than a token.

A citation from poet Nathaniel Mackey’s essay “Other: From Noun To Verb”, which I first read in “Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning”, by Cathy Park Hong, remains truly pertinent to me, in both its analysis and its declaration of intent:

There are some people who have absolutely no interest in the whole picture, nor any wish to see such nouns de-centered, yet there are more who have a great sense of curiosity and desire for discovery, but often lack any relevant or accessible sources to inform a wide angled perspective or change in grammar. Our era may be imploding with information, but there is much that remains unreported. For so long we had all been quite far away—in both physical distance, and in our expression. And it is from here that my intention speaks: simply to present a fresher voice; a different voice; a voice that speaks from a different place; a polyphonic voice composed of people of different ancestries, cultures, languages and experiences. A more balanced voice. In the hope that someone might better piece together something, and interpret it on their own. To this end, the contents of Ying Xiang’s first volume has been collected and named: gaze at the other, gaze of the other.

I could only tell my own story here, that of a perhaps transient voyager, who comes from a city at the other end of Eurasia. But there are so many more stories that need to be told, so many interesting studies that can be shared from this community, which has yet to have its voice truly heard. I’ve always seen the outside world as an opening, a destination for exploration, while growing up in a distant place. I’ve now been out here in that world for a while. And thanks to today’s modern technology and the heaps of authentic Chinese restaurants in Paris, I no longer feel so completely uprooted. Meanwhile, as my outlander’s explorations continue to unfold, I only believe even more how much our cultures reflect each other—in both our originalities and our affinities—and how important it is that we can, and keep on, inspiring one another. An attempt to further underpin this alliance, bridge understandings, and propose a broader range of inspirations, is what has prompted Ying Xiang to be—a project that takes its name from the pidgin translation of the Mandarin word, 映象. In Mandarin all words can be broken down into their composite single characters, which carry their own diverse subtleties and nuances. 映 (Yìng) could be deciphered as to reflect, to mirror (or even to shine). 象 (Xiàng) could be taken as appearance, form, image, symbol, or circumstance. Together, these two characters could signify ‘reflection’. But as always, divergences in words and ways of thinking cannot easily be rendered from one to another, inevitably something gets lost in translation.