№1 Gaze at the Other, Gaze of the Other

Fashion and Race in the Spotlight

11.01.2021,

London-based fashion journalist and editor Priya Elan discusses diversity and representation in fashion—where the races on the runway are literally the surface of the issue—advocating for change and taking the pulse of the industry, after a tumultuous 2020.

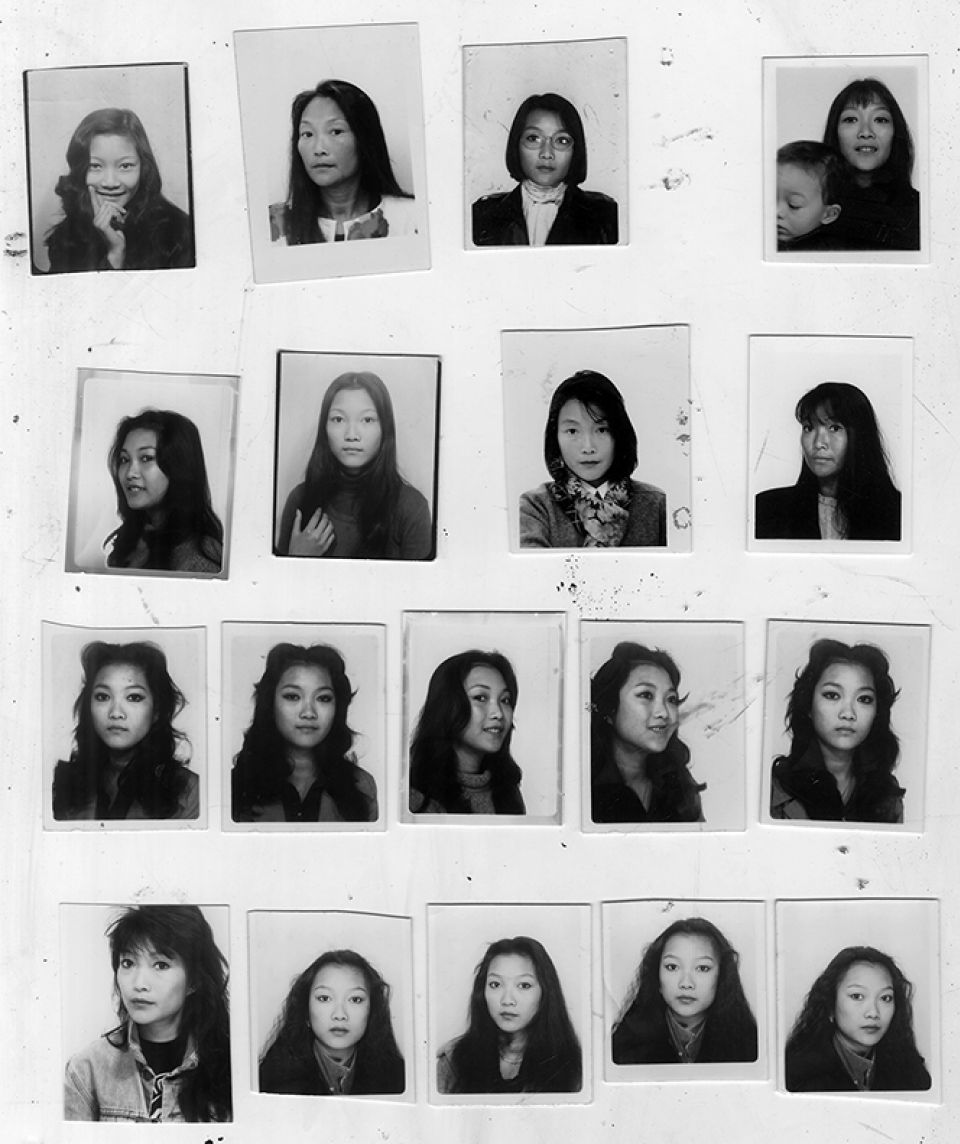

Illustration by Melody Newcomb

Joël Vacheron (JV), Priya Elan (PE)

JV

What led you to become deputy fashion editor at The Guardian?

PE

In my final year studying literature at university, a friend suggested that I apply for a job at a music magazine. I didn't get it, but the idea that this was a career blew my mind [laughs]. So, I began a postgraduate journalism course in London. After graduation, I struggled to get work but slowly got freelance gigs, one of which was at NME where I became a reporter for six years. I did a page called ‘stuff we love’, which included music T-shirt merchandise—my first crossover with fashion journalism. Many years later I freelanced for the Guardian and then applied for a job on the fashion desk, and here we are.

The music industry and the fashion industry in which I have been lucky enough to be involved have been very white. More often than not, I was the only person of color in a room.

—Priya Elan

JV

What was the atmosphere like regarding cultural diversity when you were studying?

PE

It was economically a boom time; there were exciting opportunities and changes in music, fashion, and journalism, with the internet becoming more dominant and cultural scenes happening in real life in real time.

The music industry and the fashion industry in which I have been lucky enough to be involved have been very white. More often than not, I was the only person of color in a room. After a certain point you just assume that is the norm. I'm not talking about society, but those worlds dominated by a certain class and person, more than skin color.

JV

What pushed you to address structural issues regarding race and diversity?

PE

As a second-generation child of immigrants, it’s what I observed: you have to have a little double consciousness and be hyper aware of situations and the subtle changes within them. I've always been interested in the story of outsiders, whether that's the Velvet Underground or Toni Morrison. There were a couple of writers, including Claudia Rankine, who really articulated the things I was seeing and experiencing as a person of color in the world.

I wrote about what happens on the shop floor; the experience of a sales assistant of color versus what the shop or brand presents as its ethos, and the sometimes toxic bullying and racism that goes on behind the scenes.

What was really interesting about last year, was the conversation around concepts like micro-aggression, which I read about in the work of Rankin, among others. Things that people of color had been talking about for years became mainstream and recognized as real things that happen, widening conceptually what racism is understood as, and showing how it goes into other categories.

JV

What are some specific topics discussed by minority groups, especially regarding fashion, that came out as examples of inequality?

PE

The fashion industry mirrors other industries. The main issue has been systematic racism at a corporate level, and the idea that the head of major fashion corporations is a certain type of person who looks a certain type of way. The question of how this is going to change—and if we want that—is still being asked. It’s not that simple. These things take generations to change.

Last year, I wrote about what happens on the shop floor; the experience of a sales assistant of color versus what the shop or brand presents as its ethos, and the sometimes toxic bullying and racism that goes on behind the scenes. I've seen that throughout my life, and I think props is due to the fashion world for talking about it, because a lot of these other industries don’t.

Illustration by Melody Newcomb

Class issues operate on such an unspoken level that I think no one really talks about them. Nepotism is rife.

JV

You are speaking about change that arose over a long period, critiques from the 90s that became mainstream and reachable during the Black Lives Matter movement

PE

It was interesting, and slightly dispiriting, that diversity on the runway became the be all and end all of the bigger diversity conversation. It’s an important issue, but the runway is literally the surface of the fashion industry. The systemic issue involves stuff at the corporate level that you don’t see.

JV

This elitist and hierarchical system in fashion allows one category of people to be completely in charge of decision making. Do you think the discussion around Black Lives Matter unlocked these situations, which had until then almost seemed natural?

PE

Class issues operate on such an unspoken level that I think no one really talks about them. Nepotism is rife. This is almost separate from the race thing. Each country and region have their own class symptoms that are hard to see unless you've been in those places for years. I hope that some of the conversations this year open people's eyes to forms of racism and listening. It’s more of a worry that people just don't want to listen to it anymore. In lockdown, people are in a place where they can look back on their lives. I have a lot of hope about that, because people are ready to think about change.

Edward Enninful is a dark-skinned black man who really wants to talk about certain issues and make a change within the fashion world. You can see that when you look back at last year’s British Vogue covers.

Illustration by Melody Newcomb

JV

You have covered the question of cultural appropriation in many ways. There seems to be a kind of hypersensitivity around it now. Can you help us understand how this phenomenon manifests itself? What is your take?

PE

That’s a big question [laughs]. I spoke to a lawyer for a piece I did a couple of months ago about this gray area of the visual, and how difficult it is to take legal action against that sort of appropriation. Sometimes cultural appropriation happens because the people creating are in a bubble—working with people who look and think like them. In the last 10 to 15 years, mainly thanks to the internet, we have a lot more voices speaking on cultural appropriation. The other side, if you’d like to call it that, of the internet is that there's a mishmash of times and eras, so that an image can be distanced from its context, which can lead to cultural appropriation.

JV

What about the kind of retroactive gaze we now have on formal productions, or creatives, who were not so sensitive in their time—like Jean-Paul Goude, who today is widely criticized for what he did with Grace Jones in the 80s. What do you think about being critical towards fashion designers who evolved perhaps under different conditions?

PE

It’s tricky isn’t it. Like anything—a book or a film—we experience those things in our present, so we need to be mindful of our values in 2021, and be aware of our audience and that we're looking at something with the sensitivities of now rather than then. It’s a case-by-case basis.

JV

Just before Christmas you wrote an article regarding the lack of reactivity in the fashion industry. As you said, there’s a long way to go until we might have fully diverse industries. What are your main concerns regarding the reactions of the fashion industry?

PE

I wanted to do a piece that looked back on 2020, where race was discussed in a pluralized, intelligent, multi-focused way, focused on the long-term actionable things that people may or may not be doing at a corporate level to change the things that they said they wanted to change. I wanted to ask: six months on, where are we now?

JV

What are the pros and the cons of the reactions from the fashion press?

PE

They have to do with structural issues. On the one hand you have publications that haven't changed. On the other hand, there’s British Vogue, which is a real point of advocacy. Edward Enninful is a dark-skinned black man who really wants to talk about certain issues and make a change within the fashion world. You can see that when you look back at last year’s British Vogue covers. I think it's about having different perspectives in a room and creating an openness, which is the beginning of real change.

JV

Recently there has been a rise in diversity and inclusion department among big brands. What do you think about having people in companies dedicated solely to questions of cultural diversity?

PE

I think these positions are well-intentioned, but they shouldn't need to exist, and it often feels a bit like ticking a box. It can work, but it depends on the real motives.

JV

Do you think it’s necessary to educate or provide some information that helps people to understand what's going on?

PE

Yes. People who hadn't experienced the things discussed last year, didn't know they happened. These things happen in the shadows, the silences. Educating people about what those things are is super important.

JV

What can fashion teach other creative industries?

PE

Because fashion moves so quickly, it feels like what it’s experiencing in terms of diversity is happening there first, which could be a great example for other cultural industries.

JV

How is the Asian diaspora considered in fashion, especially in Europe?

PE

I can only speak to an experience of London. Designers like Priya Ahluwalia are doing really interesting things in their designs, bringing in second-generation heritage. Especially with the newer designers, there is more of an audience for conversations around race and heritage.

PRIYA ELAN

is the Guardian's deputy fashion editor.

JOËL VACHERON

is co-founder and editorial director of Ying Xiang 映 象 Journal

MELODY NEWCOMB

is an illustrator, graphic designer, and art director, currently based out of Colorado. She has both Taiwanese and Scots-Irish ancestry, and was raised Tibetan Buddhist. When she’s not working, Melody enjoys the outdoors with her dog Beatrix.

related content

Re-examining Shanghai Calendar Girls

—

Calendar posters in China’s Republican era transformed the visual sphere of modern experience through an evolution in the representation of the female figure.

Staging the Orient

—

Professor Homay King discusses the social implications of Orientalism in cinema, the cultural construction of an East Asian imaginary, and present day negotiations of representation.

Luo Yang’s Self-Reliant Youths

—

In her photographic series, Luo Yang 罗洋 intimately depicts the everyday of China’s Generation Z, placing subcultural defiance of imposed expectations and stereotypes in the foreground, through changing bodies fixed in time.