Re-examining Shanghai Calendar Girls

Shanghai, a Prosperous City that Never Sleeps, Yuan Xiutang; Chromolithograph on paper (1930s)

1. “Republican China” and “Republican era” refer to the historical period from 1911 to 1949, when the formation of the Republic of China as a constitutional republic replaced the imperial rule of the Qing dynasty.

The Modern Girl icon, as an epitome of westernized modernity, offers a glimpse of the fusion of traditional Chinese aesthetics and cosmopolitan female beauty in modern China. It challenges the Eurocentric discourse of “modern girls” through a hybridization of foreign logic with local dress and mores, emblematic of a product of global exchange. By playing with the semiotic codes of bodily gestures, clothing and fashion, the mass media constructed an abridged mental image of the contemporary visual world—local yet global—with Chinese Modern Girls stereotypically depicted as seductive and increasingly commoditized. Yet such efforts to seduce would ultimately foster biased social perception, leading to New Women taking the Modern Girls’ place.

The opening of Shanghai to foreign trade and westerners’ settlements after the First Opium War (1840—1842) led to significant developments in its economy, society and culture, which turned Shanghai into a modern metropolis in the Republican era. Deemed a cultural matrix of Chinese modernity, urban Shanghai has long fascinated scholars with its bizarre hybrid of cosmopolitanism, nationalism and colonial modernity. Chinese scholar Leo Ou-fan Lee (1999: 63) remaps Shanghai’s cultural geography in his seminal book Shanghai Modern, where he reckons Shanghai’s modernity to be an “imagined reality” created by print media. Yeh (2007: 77) approaches the rise of modern Shanghai from an economic perspective, insisting that Shanghai’s commercial prosperity challenged the existing patterns of distribution and the norms of the cultural vista in China. It can be seen that the element of visuality, nurtured by the emerging advertising and image industry, took an indispensable role in the making of Shanghai’s glamour. It is in this light that the calendar posters, an emblem of commercial art, bloomed into being representative of Shanghai’s cultural image and modernity in the 1920s and 1930s, by virtue of these posters’ representation of Modern Girls.

Calendar posters in the Republican era not only inaugurated a new system of encoding time by juxtaposing the imported Gregorian calendar with the Chinese lunar calendar (figure 1), but also transformed the visual sphere of modern experience by representing an evolving image of the female figure. In an early example, a 1921 cigarette advert for the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company (figure 1) draws from the artistic tradition of Chinese landscape painting, and further incorporates new ingredients from Western art. The advertising girl is portrayed wearing a garb popular in the early Republican era, sitting leisurely at the riverside. The traditional loose gown of the Qing-dynasty’s code of dress, featuring wide sleeves and long length, has by now been discarded for the more practical and comfortable matching jacket and trousers, as well as skirt suits. The girl’s porcelain skin indicates a maintained reference to traditional Chinese portrait painting, in which the representation of women is to some extent distorted and stylized rather than natural.

The upcoming advertising models, dressed up in the latest fashions, more blatantly celebrated an emerging consumer culture embodied by flourishing domestic and foreign commodities such as cosmetics, fabrics, cigarettes and other fancy “modern” goods. In the mid-1920s, the legendary female Shanghainese movie star Ruan Lingyu was invited to endorse Coca-Cola, marking a great coup in Coca-Cola’s opening of the local market. In the advertising poster (figure 2), Ruan is adorned with the visual cues associated with a typical Modern Girl at that time: permed hair, high-heeled shoes and meticulous makeup. Donning a modified cheongsam (a type of traditional Manchurian dress), Ruan smiles and glances demurely at the viewer, her legs crossed in an enchanting gesture. In sharp contrast with the conservative illustration of Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company Calendar (figure 1), the Coca-Cola poster depicts the calendar lady in a more trendy and daring way: the slim-fit, gauzy cheongsam does not shy away from flattering Ruan’s body shape; her elegant posture also signals an invitation, leading the viewers to associate the commodity with an intangible promise of carnal pleasure (Barlow, 2009). Such a transformation indicates an on-going liberation of concepts of female aesthetics, illuminating the social enlightenment and women’s liberation movements that were developing in tandem in modern China. Coca-Cola, an imported commodity, took the place of the products of China’s national industry (Nanyang Brothers Tobacco) and revealed the mixed Sino-Western identity of the Chinese modern girl, who is tactfully played as an indigenous cultural symbol, to advertise westernized modernity.

Figure 1. Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company Calendar Poster, 1921.

Figure 2. A Coca-Cola poster depicting Chinese silent film actress Ruan Lingyu 阮玲玉, 1927.

Given that the calendar poster is a highly representational art form, the interpretation of its visual messages cannot be done without a decoding of the connotations embedded in its socio-cultural context. As is proposed in Mitchell’s theory of representation, political, social and subjective complexity comes into play in the dynamics of “representation” in works of literature, art, music and political theory (Mitchell, 2010). In other words, representations that work in a social and ideological context are created out of a form of “agreement” or “contract” among people in certain societies, giving form to the hidden “codes” behind aesthetic or semiotic representation. In this sense, a close reading of the Modern Girl icon can be situated in the transforming ideology of gender during the early Republican era.

The gender discourse in the Republican era mediated between the dwindling puritanical discipline of the late Qing dynasty (which the Republic replaced) and the advent of westernized modernity. In the society of the Qing dynasty, women in the upper classes were largely confined to the environment of their strict upbringing, and their consumption was also limited by social constraints (Pang, 2007). The rigid etiquette enforced by orthodox Confucian ideology decreed it unethical for females to be seen in public. In the new Republican era, images and photographs of young, vibrant females began to catch the public’s attention through a flourishing of advertising images and female-oriented magazines, which to some extent subverted the puritanical taboos. The early twentieth century also saw the abolition of foot and bosom binding under the “Natural Feet Movement” and “Natural Breast Movement”, advocated by intellectuals and mass media. As a milestone of the vigorous female emancipation movement, women’s liberation from physical bondage allowed for greater variability in fashion and aesthetics, as well as a quite literal metaphor for, and evidence of, a loosening of social constraints. This social context sheds more light on the visual codes embedded in the images we are examining: the calendar girls’ seductive manner, delicate makeup and tailored gowns turned their back against the traditional social code, revealing an aesthetic trend and movement towards westernization and cosmopolitanism.

As the anthropologist Douglas (1973) proposes, the social body constrains the way our physical body is perceived. With the emergence of a modern era of visual culture, the female body became an all-important visual symbol for conveying social values and constructing female identity, and can be perceived as a complex matrix comprising aesthetic and semiotic visual codifiers—such as body image and fashion.

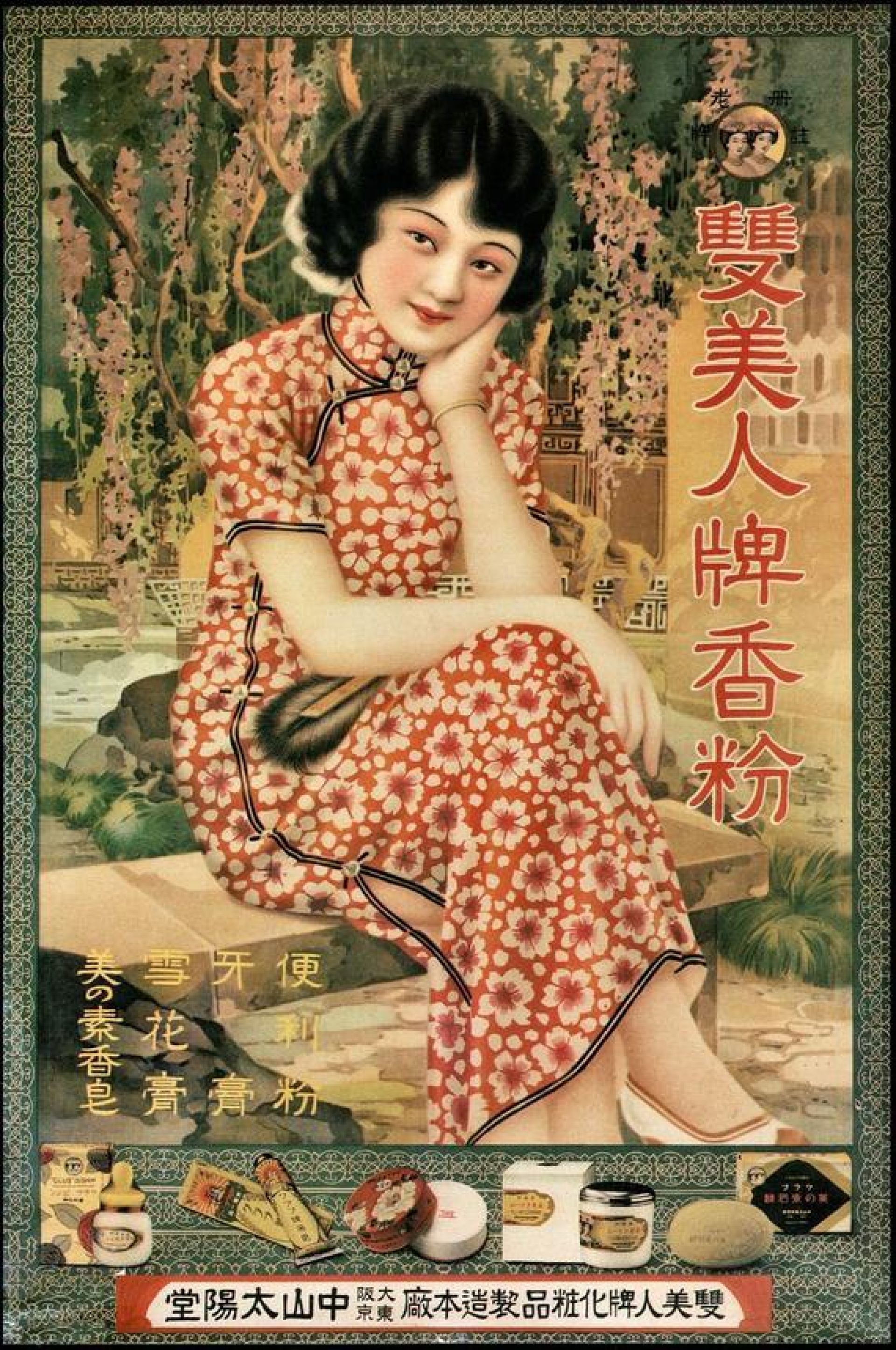

It is noteworthy that Shanghai in the 1930s witnessed a flourishing of calendar posters that promoted a Modern Girl style prizing glamour and allure, gradually replacing depictions of sedate and conservative beauty. As an important embodiment of Republican-era female fashion, the traditional cheongsam dress, also known as qipao, became a common sign in the media’s representation of Modern Girls. The cheongsam is a type of modern close-fitting dress of Manchu origin that emerged in Shanghai after the collapse of imperial rule in 1911. Under rapid westernized modernization in both politics and economy, modern women, represented by movie stars and schoolgirls, began to strive for a reform in clothing, giving birth to this iconic garment. As co-education was introduced starting from 1920s, intellectual women gradually shed the traditional, ornate robes and adopted the early form of cheongsam which evolved from a type of androgynous men’s garment called changshan. Cheongsam was therefore endowed with the modern value of gender equality since its birth.

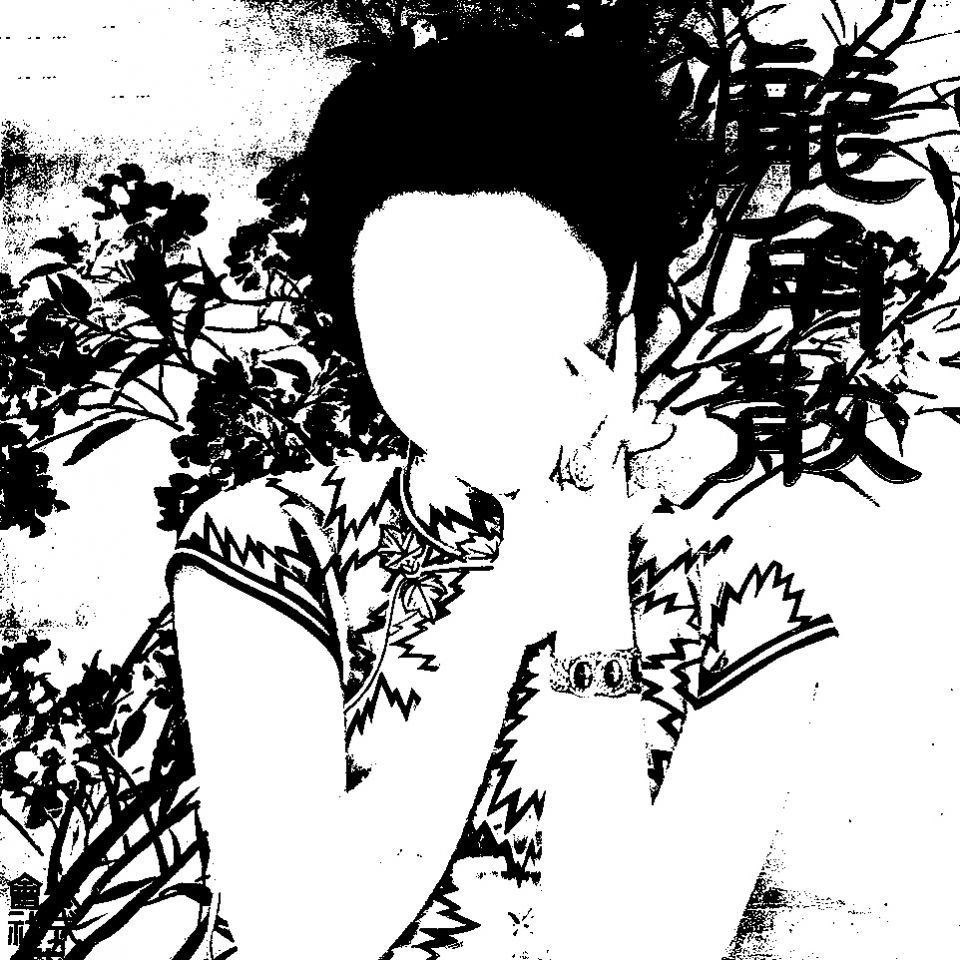

The 1934 calendar poster of the Yuanhe Trading Company (figure 3) testifies to this trend by featuring a Modern Girl wearing a more stylish gauzy cheongsam. The female model sits in a rather seductive posture in which her underskirt looms, with high-heels pointing suggestively towards the advertised products. The comparison between the Coca-Cola advert (figure 2) and the Yuanhe Company poster (figure 3) reveals transformations in the aesthetic standard of the cheongsam: the side slit tended to move higher up to the hip over time, exposing more of the female body. Although both dresses embody a hybrid fashion of Western and Chinese style, the piece of cheongsam in figure 3 is less conservative and secretive about female sex appeal, more explicitly tempting the male gaze. With her head propped up on one hand and legs crossed, the calendar lady in figure 3 blatantly shows off her graceful figure. The crossed legs, an arguably “unladylike” bodily posture at that time, remains consistent across the calendar posters of multifarious goods. A 1930s advert for Japanese face powder (figure 4) portrays another cheongsam girl in a strikingly similar manner, despite different backdrops, commodities and artistic styles.

Figure 3. Calendar Poster of the Yuanhe Trading Company showing a women beside two wine glasses, possibly communicating a message of invitation to a potential male companion (1930s).

Figure 4. Calendar Poster for Shuang Meiren (face powder) showing a woman with her legs crossed, an arguably “unladylike” bodily posture at that time (1930s).

According to a 1930s “conduct code” article in The Modern Lady (Jindai Funu), women’s crossed legs were deemed an ugly pose inappropriate in public places (Ying, 1930: 4-5). This article cautions that women should mind the effect of their “every action” and observe a certain “modern postural etiquette” in public (Ying, 1930: 4). As Dal Lago (1973: 108) comments: “Even the bodily postures may signal an achieved status of modernity, highlighting with its visual and moral connotations the constructed image of the new women.” In this sense, the calendar girls’ bodily posture constitutes a violation against the social norms at that time. Although the removal of Qing dynasty taboos, for the first time, allowed women to display their bodies and actions to the public gaze, Confucian gender ideology continued to discipline their deeds well into the Republican era.

The interpretation of the calendar lady figure, a gendered representation of her time, cannot neglect the socio-political environment and its gender ideology. The changing gender ideology in the Republican decades gave birth to two female archetypes, namely, the politically progressive New Woman and the arguably decadent Modern Girl, both of which were prevalent in literature, cinema and pictorials (Stevens, 2003). The New Woman, often associated with leftist intellectuals, stood for the discourse of female emancipation and the nation’s request for modernity (Stevens, 2003). The Modern Girls, meanwhile, attracted the public’s gaze primarily through the means of, and as a product of, advertising, wherein female images were manipulated and designed by merchants and commercial artists. The images of calendar girls, in particular, were highly crafted in an attempt to create an ideal association with new fancy modern commodities (Lago, 2000). In this light, the calendar girls’ unladylike, seductive bodily poses would then become a motif connoting their sex appeal and even a suggestion of casual sexual behavior, catering predominantly to the desire of a male audience or male consumers.

Alongside the trappings and body image of female models, the backdrop and commodities also serve as important visual cues in these adverts. Upon closer examination, we can notice two wine glasses alongside the Haig liquor being advertised (figure 3), possibly communicating a message of invitation to a potential male companion. The Coca-Cola poster (figure 2) adopts the same visual cue to imply the existence of an invisible male partner—or rather, the sexual availability of the calendar lady through her suggested entertainment of a guest. As Barlow (2009: 288) claims, “sexualized modern girls embody the promised pleasure of industrial society”. Playing tactfully with such visual symbols and the cultural connotations behind them, the advertisers arguably sought to arouse an association between the seductive calendar girls and the sensual pleasures promised by the imported modern goods. The Modern Girls, portrayed as the carriers of commercial messages, gradually descended to themselves being marketable objects as such. The posters for Lactogen Milk Powder (figure 5) and Mosquito Coil (figure 6) further illuminate this insight. In both pictures, the calendar ladies are depicted as sexually attractive by underscoring their provocative smiles, body gestures and graceful feminine curves. However, it is noteworthy that their images have barely any association with the commodities being advertised—neither milk powder nor mosquito incense; rather than endorsing the commodities, the glamorous, modern-looking calendar girls serve to render an atmosphere of modern consumerism. In this sense, Modern Girls in such commercial adverts could be perceived as “empty signifiers”, whose significance depends more on the dominant discourse of consumerism than on the specific commodities themselves.

Figure 5. Calendar Poster for Lactogen Milk Powder, 1934.

Figure 6. “Miss Happiness” poster, an advertisement for Indanthrene cloth, designed by Liang Neng for IG Farben, China, 1930s.

Figure 7. Advertisement for “Three Cat” Cigarettes, 1930s.

2. May Fourth Movement: anti-imperialist intellectual revolution and political reform movement that grew out of student protests on May 4th 1911 against Japan’s commercial and territorial claims on Shandong.

3. New Culture Movement (1910s—1920s): the progenitor of the May Fourth Movement, criticized feudal despotism and promoted new Chinese culture based on western ideals of “science” and “democracy”.

Besides an iconoclastic visual display of feminine charm through pictorials and adverts, the new Republican era also undid restrictions on female consumption in the public sphere (Pang, 2007: 105). Under the vigorous May Fourth2 and New Culture Movements,3 Republican-era women were encouraged to enter the public realm in unprecedented ways, which included assuming the role of modern consumers. Such emancipation of female purchasing power is evidenced within the evolving images of calendar girls as well. An Indanthrene (Indan shilin) fabric advert titled “Miss Happiness” (figure 6), in particular, portrays a self-confident modern lady in modified sleeveless cheongsam. The captions make an explicit assertion that she is so joyful because she wears dresses made of Indanthrene fabric, implying the autonomy of modern women to dress up, to consume by freewill, and to enjoy a flamboyant culture of consumption. Comparably, the “Three Cat” cigarette poster (figure 7) presents a similarly cheerful and confident modern female consumer, holding a cigarette in a graceful manner. Nevertheless, the smoking lady’s outfit is suspiciously skimpy for visual display at that time, betraying the advertisers’ attempts to appeal to the male gaze.

As a beguiling icon of modern Shanghai, the Modern Girl in visual media set a precedent for Chinese women to expressively display their body image in public realms, and was gradually blended into the cultural image of Republican Shanghai as a whole. The Modern Girl image came into shape under a constant East-West cultural interplay, in which Eurocentric aesthetic ideals monopolized the discourse of “modernity” and “beauty.” Under the global tide of Modern Girls, the increasing visibility of female figures and the westernized aesthetic trends they embodied ushered in a liberation of socio-cultural ethics in Republican China. Meanwhile, the bizarre hybrid of traditional Chinese aesthetics with westernized ideals gave birth to the cosmopolitan beauty of Shanghai calendar girls, shedding light on marginalized national narratives of modernity and beauty. Nevertheless, as a creature of media representation under the male-dominated capitalist culture, the calendar girl image is inevitably adorned with stereotypical visual cues associated with female passiveness and sexuality, tactfully appealing to a male gaze. Such a media parallax reinforced the biased social perceptions of Modern Girls, leading to the gradual alienation of the Modern Girl archetype from the mainstream female ideal, as the politically progressive New Woman, and ultimately, the national discourse of modernity, assumed a new pose of its own.

References

• Cheuk, P. T. et al., ed. (2004). Chinese Woman and Modernity: Calendar Posters of the 1910s—1930s. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing.

• Liangyou [Young Companion]. (1926—1945). Shanghai: Liangyou tushu yinghua gongsi.

• Yi, B., Liu, Y. & Gan Z. (1995). Lao Shanghai guanggao [Old Advertisement in Shanghai]. Shanghai: Shanghai huabao she.

• Zhang, Y. (1994). Lao yuefenpai guanggao [Old Calendar Advertisement]. Taiwan: Hansheng zazhi she.

Secondary Sources

• Barlow, T. E. (2009). “Buying In: Advertising and the Sexy Modern Girl

Icon in Shanghai in the 1920s and 1930s” in A. E. Weinbaum et al. (Ed.) The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization (pp. 288-316). Durham: Duke University Press, 2009.

• Douglas, M. (1973). Natural Symbols: Explorations in Cosmology. London: Penguin Books.

• Dal Lago, F. (2000). “Crossed Legs in 1930s Shanghai: How ‘Modern’ the Modern Woman?” East Asian History, 18(19), 103-144.

• Lee, L. O. (1999). Shanghai Modern: the Flowering of a New Urban Culture in China, 1930-1945. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

• Mitchell, W. J. T. (2010). “Representation” in F. Lentricchia et al. (Ed.) Critical Terms for Literary Study (pp.11-22), Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

• Pang, L. (2007). The Distorting Mirror: Visual Modernity in China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

• Stevens, S. E. (2003). “Figuring Modernity: The New Woman and the Modern Girl in Republican China.” NWSA Journal, 15(3), 82-103.

• Yeh, W. (2007). “Visual Politics and Shanghai Glamour” in Shanghai Splendor: Economic Sentiments and the Making of Modern China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 51-78.

• Ying, L. (1930, April). “Ni dongde zenyang qu zuo, zhan, he zoulu rna?” [Do you know how to sit, stand and walk?]. Jindai funv [The Modern Lady], 16, 4-5.