Looking into People’s Eyes

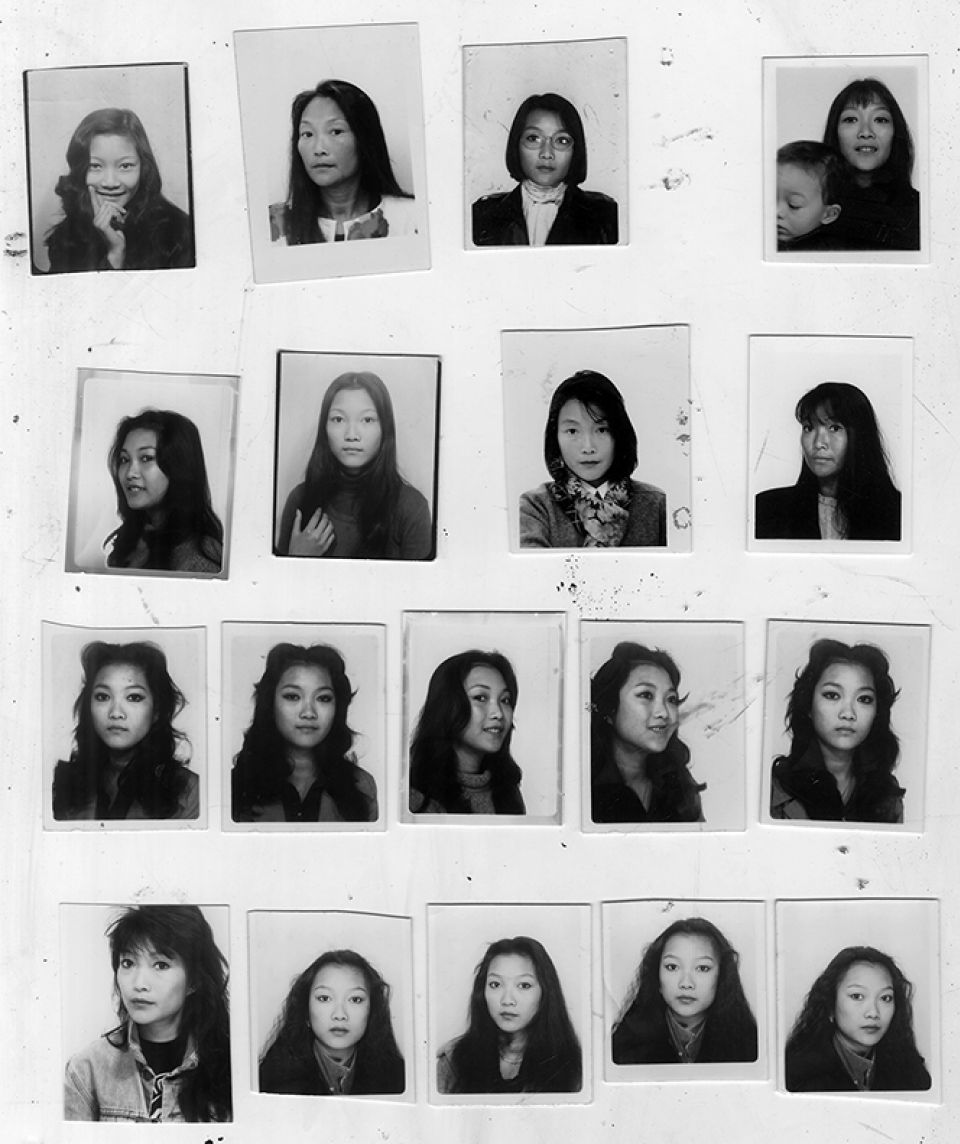

Illustration by Li Ya Wen 李雅雯

Whiskey Chow, Masculinism, Rich Mix, London, 2018. (image credit: Orlando Myxx)

Whiskey Chow, M.A.C.H.O, Fierce Festival 2019, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. (image credit: Paul Gregory)

Whiskey Chow, Purely Beautiful New Era, Friday Late: Sino Flux, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, November 2017. (image credit: Hydar Dewachi)

Whiskey Chow, Whiskey the Conqueror, Tender Loin #7, Toynbee Studios (Artsadmin), London, January 2017 (image credit: Greg Goodale)

Whiskey Chow, Unhomeliness, Tate Modern, London, 2018. (image credit: Alice Jacobs)

Whiskey Chow, The Moon is Warmer than the Sun, Chinese Arts Now Festival 2019, London. (image credit: Lidia Crisafulli)

Queering Now, Rich Mix, London, 8th February 2020. (poster design: Sha Li)

Fatima Al Qadiri, Asiatisch, Hyperdub, 2014