An Archeology of the White Gaze

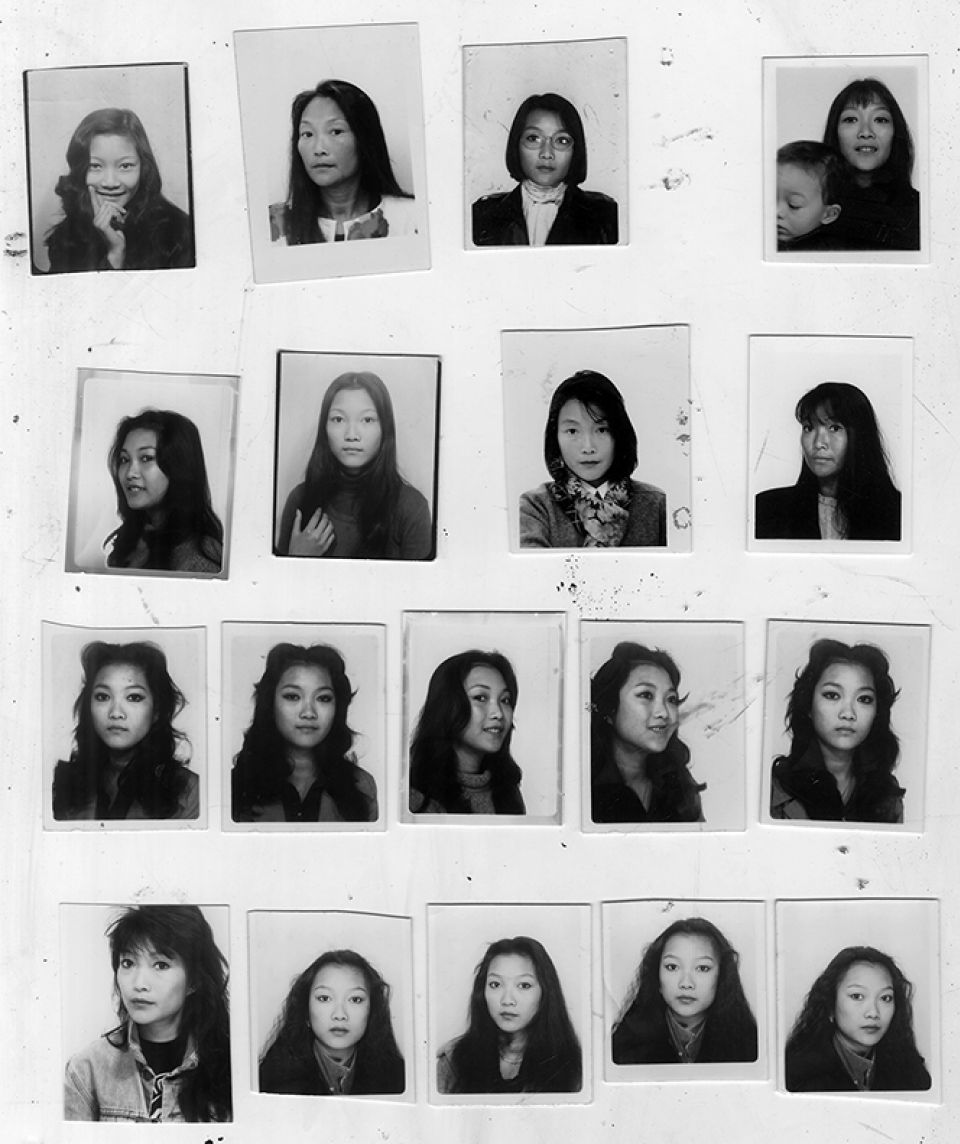

Lau Wai 劉衛, The Memories of Tomorrow/I'm just Wan Chai girl (2018) 135cm × 75.7cm, archival pigment print

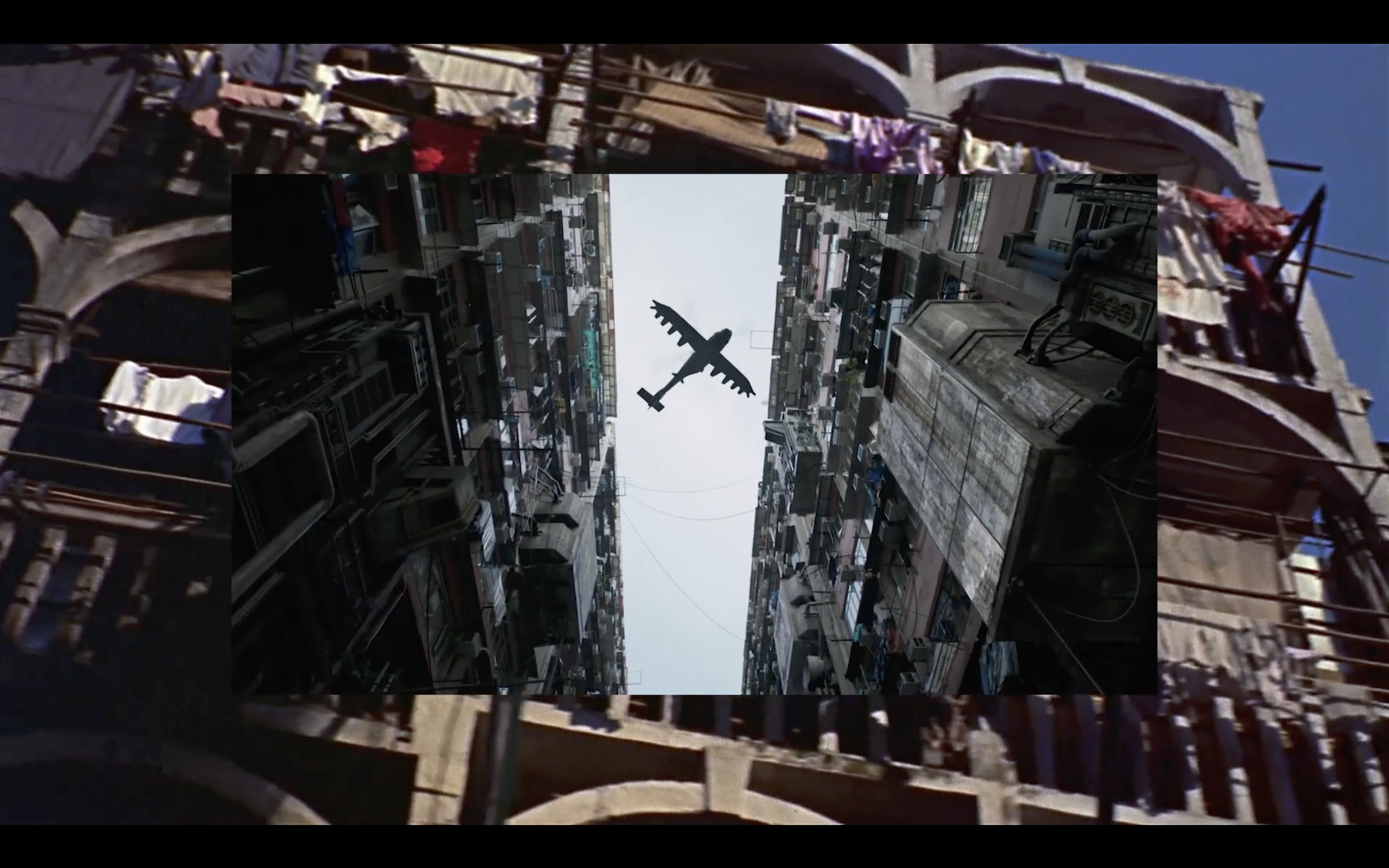

Arriving on an overly crowded Star Ferry, walking through the bustling streets and market, a well-dressed Western man, a conspicuous outsider carrying a leather suitcase, cannot help but observe the total difference and novelty of the place in which he has landed. This Oriental world has some sort of dangerous romance hidden beneath it. Even the indifferent Asian-looking girl on the Star Ferry seems to open up a new reality. This is the beginning of the movie The World of Suzie Wong (Richard Quine, 1960); a film adapted from a British novel, and shot in Hong Kong more than a half-century ago, demonstrating an early yet significant phase of how Hong Kong was interpreted, constructed, and delivered to worldwide audiences. More than 50 years later, in Hong Kong shot scenes from Ghost in the Shell (Rupert Sanders, 2017)—a movie supposed to be set in the future—again two Western characters walk through these same bustling streets and markets. The background has not changed much with the passing of time, but somehow, strangely, the dated surroundings have become a set for the future.

Hong Kong artist Lau Wai’s video work Walking to Nam Kok Hotel (2018) has double storylines and combines the two movies mentioned above. By overlaying scenes extracted from Ghost in the Shell on top of The World of Suzie Wong, with the images from Ghost in the Shell constantly flashing, the viewer focuses on concentrating and closely comparing the details of both movies, determining what has changed and remained the same in both the urban background and the Oriental fantasy. Apart from the updated fashions of the Western characters in the newer movie, the chaotic streets of Hong Kong and its vendors somehow retain the colonial aspects of the earlier film. The old Oriental look and culture has certainly been used to satisfy some viewers’ imaginations and clichés of how the world unfolds in the East.

Lau Wai 劉衛, Walking to Nam Kok Hotel (2018), single-channel video, colour and sound, 03' 24", video still

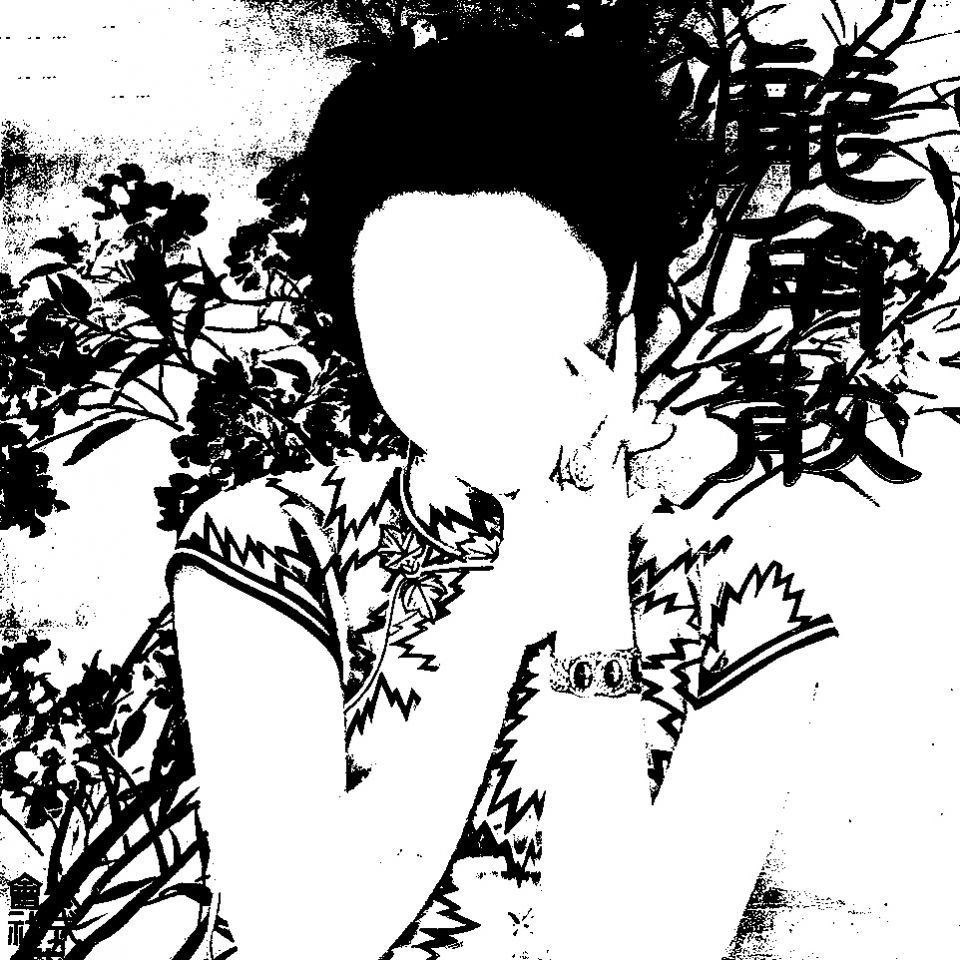

The video work Walking to Nam Kok Hotel is part of the series The Memories of Tomorrow I & II. A similar approach has been applied across the whole series, which includes both still and moving images. For I am just Wan Chai girl, My name is Gweny Lee, and Queens Road West 040, Lau has added bizarre surreal elements onto existing vintage postcards and photographs. These series focus on how Hollywood cinema from 1950 onwards has depicted the concept of the ‘Orient’, particularly in relation to Hong Kong, as well as how these notions and fantasized representations have functioned in the process of forming the identity of the depicted cities, regions, and ethnic groups.

Most of Lau Wai’s important work consists of image-based research and study within film archives, detailing how the accepted ‘white gaze’ has been constructed and projected over the decades. The ‘white gaze’ in cinema has existed as an issue since the beginning of film history. One of cinema’s earliest movies, The Birth of a Nation (1915), offers a key example of how films could be commercially and artistically successful and influential but project a certain stereotyped gaze on a minority group (in that film’s instance, African Americans). Through the years of the film industry’s development, when Western cinema has looked to the East, Lau’s intensive research on film archives finds that from 1980 onwards cinematic depictions of the ‘Orient’ have frequently been combined with futuristic imagery, starting from the growing global influence of cyberpunk and anime culture, “…often combined with the many cliché, pre-existing stereotypical elements associated with the ‘Oriental’.” Thus, in Lau’s series The Memories of Tomorrow I & II, she tends to use various materials to generate uncanny scenarios, traveling through time in an attempt to question the processes of the formation of representation.

Lau Wai 劉衛, I am invincible...on the screen/False motion tracking (2019–2020), 2-channel video, color and sound, 03’13”, video still

Lau’s latest video work, the split-screen I am invincible…on the screen/False Motion Tracking (2019-20) is an extension of the visual research of The Memories of Tomorrow I & II. The visual discomfort of watching I am invincible… is similar to watching Walking to Nam Kok Hotel, as the video creates a continuous paradox and intertwined dilemma. For the new work, Lau has gone through eleven Hollywood movies and American TV series produced from the late 1930s to the late 1980s, centered on the portrayal of characters of Chinese descent, and stories filmed in Hong Kong. By using ‘deepfake’ synthetic media technology, through a mobile app, on one screen Lau becomes the characters in animated stills taken from these productions, and rewrites their lines. On another screen, we see Lau’s body covered with fake data tracking points, as if the deepfaked scenes are the product of 3D capture. While Lau moves her body or tries to vocalize in one video, the other video of extracted film scenes responds simultaneously to her movement. The awkwardness and unfamiliar visual experience works to strengthen viewers’ attention to the behavior of Chinese characters in television and film. Lau Wai questions further who has the power to control these bodies, and in so doing create representations of race, gender, sexuality and class. The film productions that continue to be made and distributed, fast and wide, contain endless content and gazes, which demand to be similarly examined and scrutinized.

Lau Wai 劉衛, The Memories of Tomorrow/IMy name is Gweny Lee (2018) 135cm × 75.7cm, archival pigment print

Exhibition view of the exhibition Relativity Hypothesis, J:Gallery, Shanghai, China, 2018