Staging the Orient

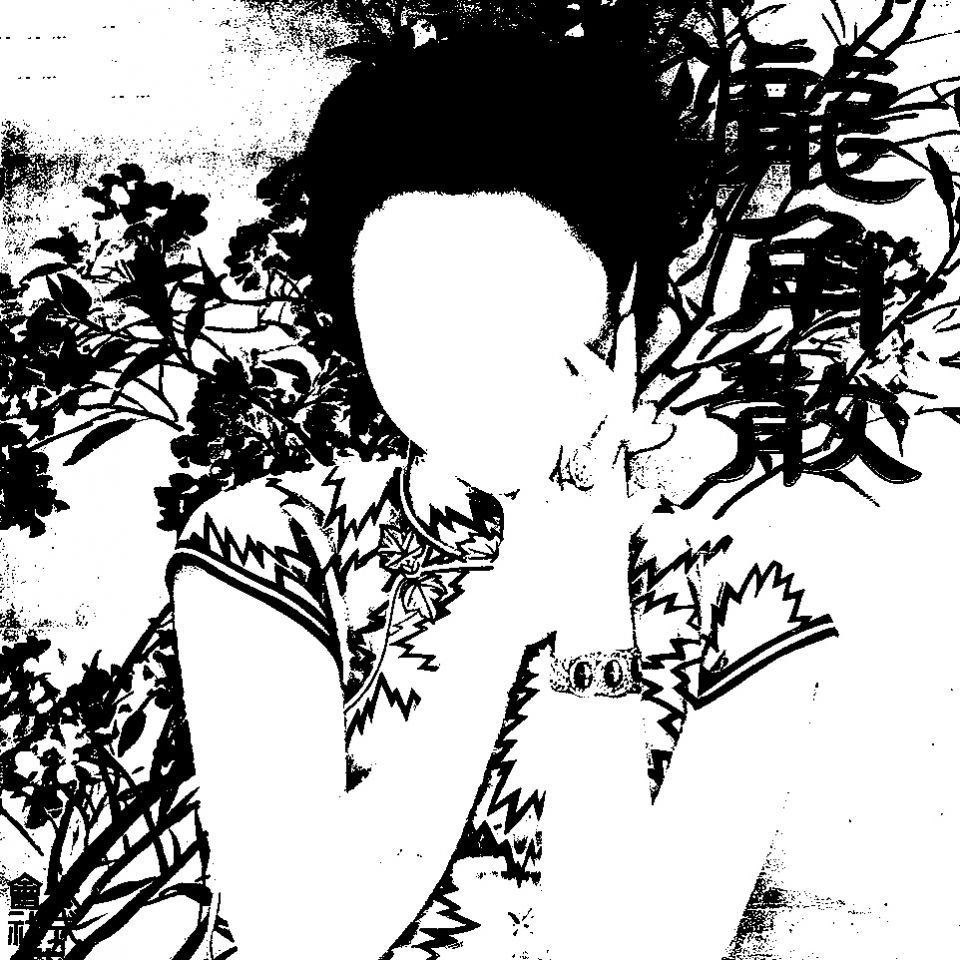

Illustration by Shuhua Xiong 熊姝华

Scene from Broken Blossoms, or The Yellow Man and the Girl. 1919. USA. Directed by D. W. Griffith.

Martha Vickers playing the character of Carmen Sternwood in The Big Sleep (USA, 1946, Dir. Josef von Sternberg).

Posters for Josef von Sternberg’s 1932 melodrama Shanghai Express, and 1952 film noir Macao.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Le Charmeur de Serpent (The Snake Charmer), c.1879, oil on canvas, 82.2cm × 121cm (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts)

Los Angeles in 2019, as depicted in Blade Runner, 1982, Dir. Ridley Scott (Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext/Warner Bros)

Rihanna's Met Gala dress in 2015, designed by Guo Pei for the theme: “China: Through the Looking Glass”. In an interview for The Cut, the fashion designer stated: “The focus and the attention paid to this dress will make it remembered by the world—[what] I want is to make them remember. ... It is my responsibility to let the world know China’s tradition and past, and to give the splendor of China a new expression. I hope that people do know China in this way”. (Kathleen Hou, Exclusive: Chinese Couture Designer Guo Pei Releases M.A.C Collaboration, The Cut, 2015)

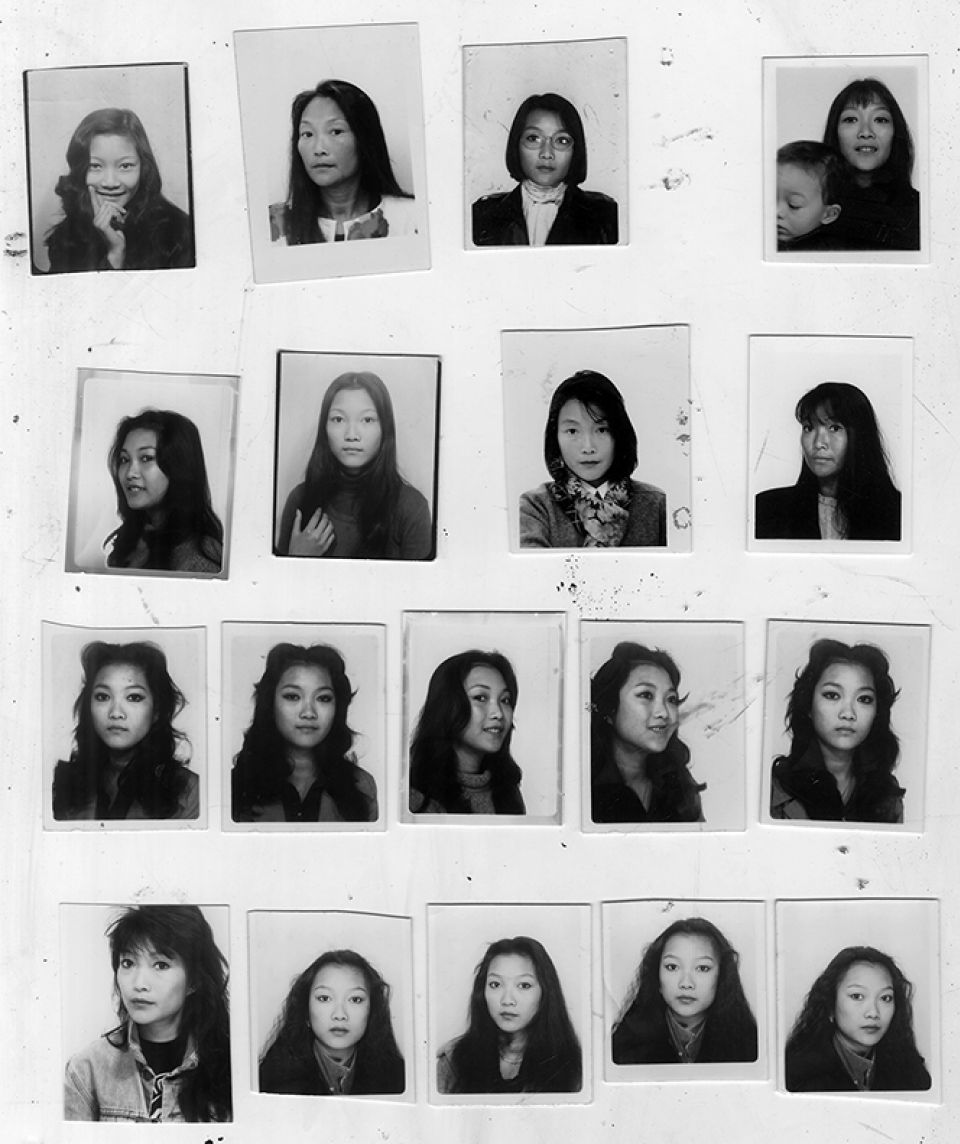

Anna May Wong in The Toll of the Sea, USA, 1922, Dir. Chester M. Franklin (courtesy: UCLA Film & Television Archive, Los Angeles)