№1 Gaze at the Other, Gaze of the Other

Introducing and Curating Fashion in China

22.10.2020,

We had this conversation via WeChat with Shanghai-based Chinese fashion researcher and curator Pooky Lee 李宠. Lee’s background in fashion blogging, publishing, and designer brands includes a sojourn in the UK where he studied fashion curation. Here he shares his approach to communicating fashion in today’s China—set to be the world’s biggest luxury market—and sheds light on the actual status of an industry heavily dependent on celebrity culture.

View of M/Made in Shanghai, Power Station of Art, September 27 2020 to April 18 2021, Shanghai (Courtesy of the Power Station of Art).

Yueshu Jian (YJ), Pooky Lee (PL), Joël Vacheron (JV)

YJ

Could you tell me about your background and how you got started in fashion?

PL

I spent my childhood in Jilin in northeastern China, and then went to Jilin University where I majored in advertising and marketing. In the first year I fell in love with fashion. I was extremely interested in how it could be a tool for people to communicate with each other. I wrote for magazines and online platforms and after graduation I got a job at a fashion publication called Modern Weekly, a very progressive magazine here in China, where I was made Fashion Features Editor in 2014. Very soon I realized that creating two-dimensional printed fashion spreads could feel restrictive. I thought the format limited the value of the message.

YJ

How did you end up doing fashion curation?

PL

That was also the time when fashion exhibitions and curating fashion became popular, globally, after the success of the blockbuster exhibition Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Regarding China, brands like Dior and Louis Vuitton also used exhibitions as promotional marketing tools to connect with Chinese customers.

I had the chance to interview Andrew Bolton, Head Curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, and asked what advice he had for aspiring fashion curators. He told me that there was a special course at the University of the Arts London, so I applied. It was very niche, and still is today, to major in fashion curation. In my year we only had four students but two professors. We had the luxury of spending a lot of time with professors and scholars to really grow into the discipline. I stayed in London for almost two years, which changed my idea of fashion. Traditional fashion media in China had somehow got stuck, and became heavily dependent on celebrities, and the topics they covered weren’t really relevant. Through fashion curating, I began to think of fashion from a much broader perspective, understanding the relationship between garments and the body, space, and social context.

When I returned to Shanghai, my first job was as a studio manager for the fashion brand XU ZHI, whose designer was based in London. I oversaw nearly all aspects of the brand, which gave me a modest understanding of how the industry functions. After that I became group fashion curation project director at Huasheng Media Group. I didn’t stay there very long. I resigned last year to start my own fashion curation studio, ExhibitingFashion.

Traditional fashion media in China had somehow got stuck, and became heavily dependent on celebrities, and the topics they covered weren’t really relevant.

—Pooky Lee 李宠

YJ

What is your latest project?

PL

You look to consumers and industry professionals to challenge how you work as a creative director for fashion brands. In the past, the garment was the most important item. Now it's the visual language. In 2018, I got the chance to work with Power Station of Art in Shanghai on a collaborative curatorial project of my choosing, and the name of M/M (Paris) immediately came to my mind. I have always loved how their graphic design showcases a new way to look at fashion. And that’s why I invited them to launch M/M (Paris)’s first exhibition in China, M/Made in Shanghai (2020—21). The museum’s staff were very involved and interested in launching something ambitious. Visitors liked the interactive design that moved beyond two-dimensional posters, though some found it too social media friendly, that there was little academic analysis. Initially we did want to launch an analysis-driven examination, but with the pandemic’s restrictions on travel and budget, we went in a more playful direction so that the public could have some fun after months of lockdown—for it to be a more mutual experience rather than an artist telling you what to do.

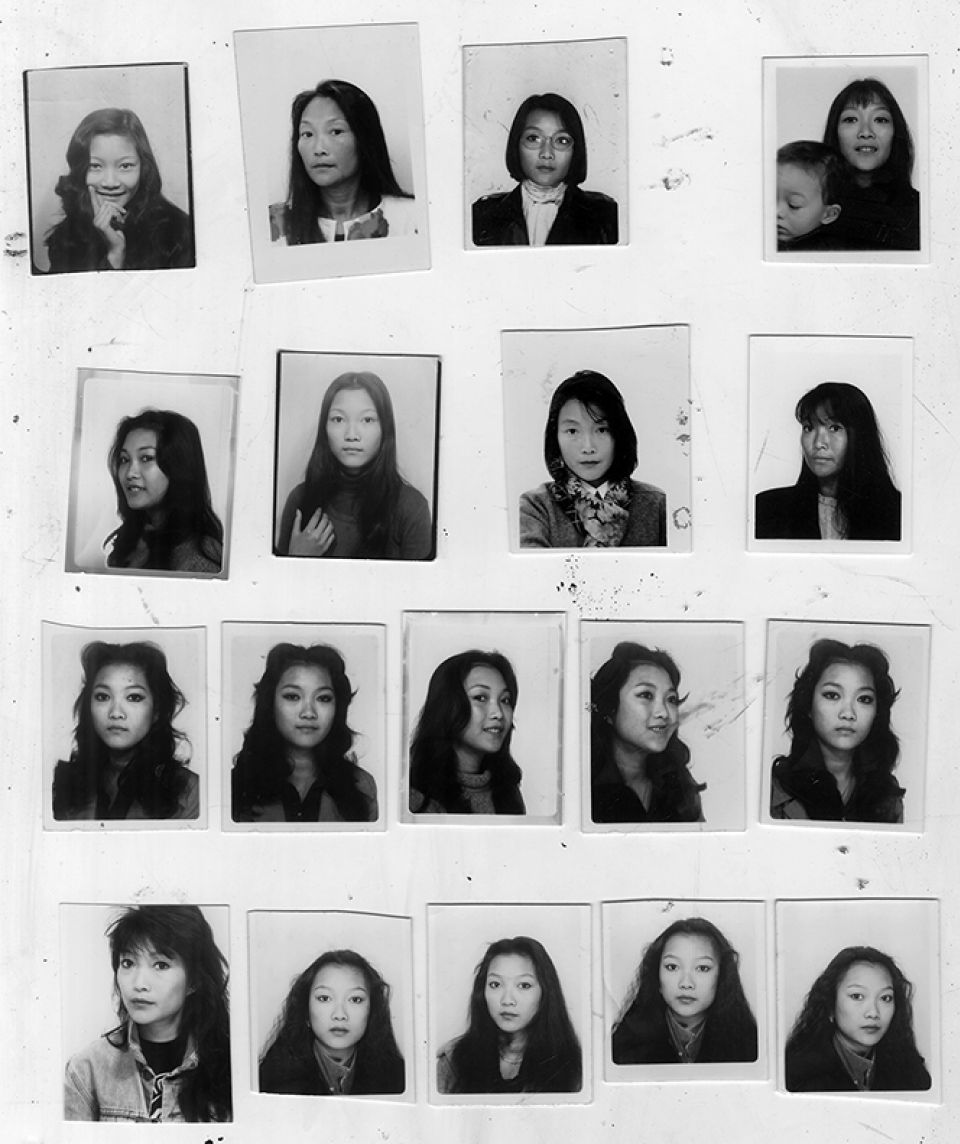

Views of the exhibition New China Chic: A Fusion of East and West, Power Station of Art, October 11 to 14 2018, Shanghai.

YJ

Could you tell me more about an earlier exhibition you curated, New China Chic: A Fusion of East and West, which covered Chinese design more specifically?

PL

New China Chic, at Power Station of Art Museum in 2018, was commissioned by Shanghai Fashion Week itself. It was a more traditional fashion exhibition about younger Chinese designers. Most of them study overseas and bring back what they have learned—this kind of Western way of understanding fashion so we featured those based abroad or who showcase their work there. For example, we featured works by Vivienne Tam, the most famous designer with an Asian background in the late 1990s. We explored these backgrounds within the new Chinese fashion identity, to consider how cultures clash with each other to create something new. If fashion is a language, how can it speak to different audiences?

YJ

With little travel at the moment, Chinese fashion is getting more attention nationally as editors concentrate on local designers. What are the advantages of local designers?

PL

Understanding of the local market. Unless you actually live or work here there is a misunderstanding overseas.

JV

Does the new generation still feel they need to come to study in Europe to make a career?

PL

Yes. The success stories of the new generation indicate a path, showing that if you want to achieve a certain format or model you need to study fashion overseas—especially at famous schools like Central Saint Martins or Royal College of Art—and then come back to China, which isn't necessarily a bad thing. Because fashion education in China is still very production-led, which doesn’t really educate you to design or think from fashion or creativity’s perspective.

To the Chinese public, fashion, especially Western fashion, still represents prestige, wealth, that you are part of a certain social class—that’s why consuming luxury fashion is on the rise. At the same time fashion in China is closely connected with celebrity culture. Nearly all the major fashion publications feature celebrity: a marriage between the luxury brands, celebrities, and their fans. Fashion media is dominated by the so-called big five in China: Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, Elle, Cosmopolitan, and Marie Claire. Any actor that appears on the cover is counted as part of their achievements. That's how fashion came to represent fame in China.

The success stories of the new generation indicate a path, showing that if you want to achieve a certain format or model you need to study fashion overseas—especially at famous schools like Central Saint Martins or Royal College of Art—and then come back to China, which isn't necessarily a bad thing.

YJ

Chinese magazines prefer to feature Chinese celebrities over American celebrities.

PL

People are naturally more familiar with people they can relate to. In my experience it doesn't really make a lot of sense to feature top actors from other countries. Usually the fashion brand chooses what to put on magazine covers. From the editorial point of view, they want to put different figures on the cover, but this is interrupted by the brands who pay for the ads.

JV

Does social media follow the same kind of rules, or do you deal differently with representation there?

YJ

What exhibition would you like to bring to China next?

PL

At my fashion curation studio, we not only work with artists to launch exhibitions but also have our own research and curation plans. This year we tried to connect Chinese and Italian designers to link these two fashion industry systems aesthetically and culturally. Another would be to feature SHOWstudio, the live-streaming fashion site founded by photographer Nick Knight, where I did my internship back in London, and to launch an exhibition about their fashion film projects over the last twenty years. I have always been a big fan of Ren Hang, whose work features a lot of nudity and who sadly committed suicide in 2017. There is something very interesting about how he portrays clothes and participation with his models. In Milan, at boutique 10 Corso Como, they did something earlier this year in the store, but they didn’t really show any original prints, only magazines.

With respect to restrictions in China, I think it comes down to your connection with the authority or the type of institution or the artists. I saw a recent exhibition that featured nudity, without censorship. There is a fine line between art, nudity, and pornography according to the Chinese authorities. The most sensitive issue is politics. The singer Björk is sensitive and taboo here, and we couldn't feature any content of her in the M/M (Paris) exhibition or catalogue.

Poster for A Material Utopia Exhibition, October 10 to 13 2020, Shanghai

YJ

Who is your public? How will you grow your niche?

PL

I’m based in Shanghai. The people here are in the habit of going to museums and galleries, which have so far been attracted to big names like Dior. I haven’t done exhibitions in other cities in China, but according to my colleagues they don’t have this environment. We don’t necessarily think about the audience. I always believe that good content with the right marketing and promotion will attract people. I see my role as being to educate the public about the cultural and social significance of fashion rather than its consumerist aspects. We want people to come to appreciate the deeper meaning of fashion, which is why we have exhibitions as well as lectures. Students can always come to lectures for free, so they can be inspired to produce something interesting.

YJ

A lot of exhibitions are related to the Western context. Are you planning to add more Chinese content?

PL

Yes. Contemporary Chinese fashion is something I’ve always been interested in. We helped organize a conference in collaboration with scholars Wessie Ling and Simona Segre-Reinach last year and invited local designers. Also last year we helped the Victoria & Albert Museum in London enrich their Chinese fashion collection, by encouraging them to visit the studios of local designers to increase the visibility of Chinese fashion. I do wish to organize an exhibition dedicated to Chinese content in the future.

This conversation took place on 22 October 2020, via Wechat.

POOKY LEE 李宠

is a Shanghai-based fashion curator and creative consultant. He graduated from the University of the Arts London with a master's degree in fashion curation. His studio, ExhibitingFashion, regularly curates exhibitions, seminars, and workshops on fashion and culture subjects. Lee's on the editorial board of the academic journal Fashion, Style and Popular Culture.

YUESHU JIAN 见悦书

is the founding director of Ying Xiang. She has been working in the fashion industry for over a decade between China and France, and currently lives and works in Paris.

related content

Clothing as Vessel

—

Artist Bruno Zhu talks shop, reflecting on a year of personal revelations in 2020, navigating identity, clothing as a vessel for failure, and essential/nonessential languages.

Luo Yang’s Self-Reliant Youths

—

In her photographic series, Luo Yang 罗洋 intimately depicts the everyday of China’s Generation Z, placing subcultural defiance of imposed expectations and stereotypes in the foreground, through changing bodies fixed in time.

Staging the Orient

—

Professor Homay King discusses the social implications of Orientalism in cinema, the cultural construction of an East Asian imaginary, and present day negotiations of representation.