East Meets West in Chinese Fashion Culture

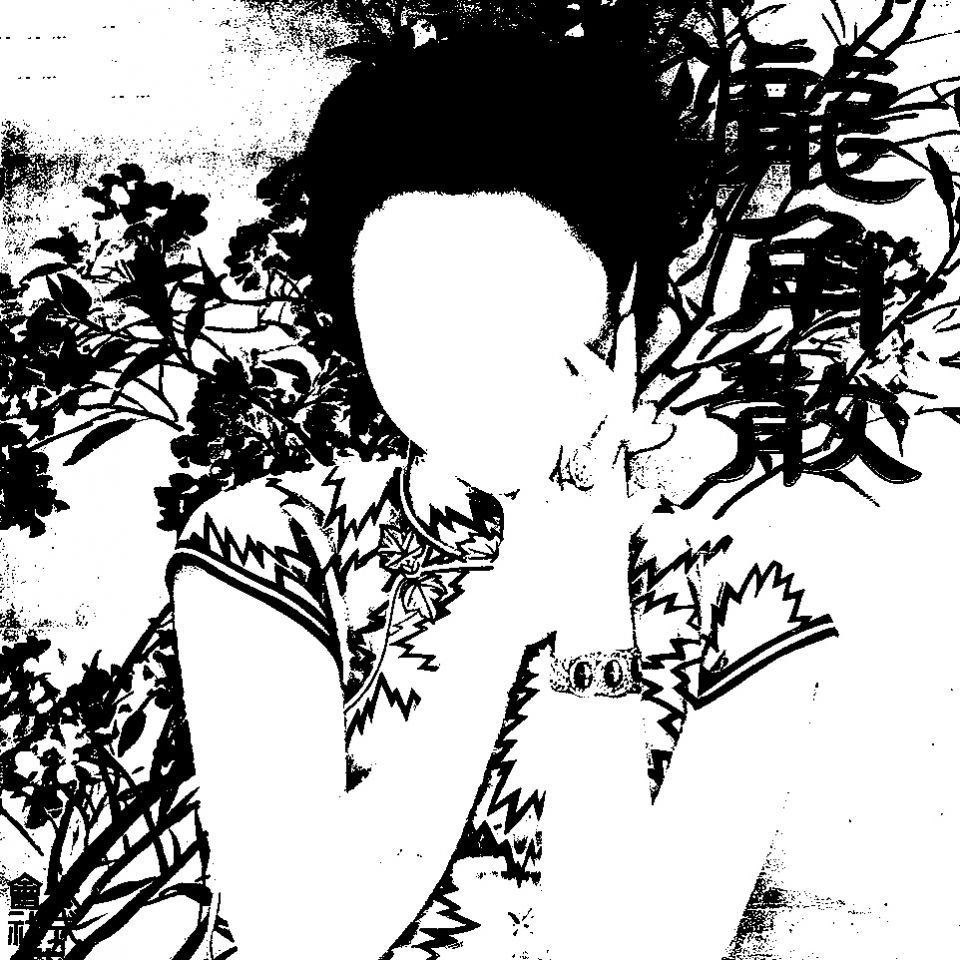

Maggie Cheung wearing a cheongsam with floral motifs mirroring her surroundings, in Wong Kar-Wai's 2000 movie "In the Mood for Love". (Credit: IMDB)

Historically speaking, since the end of the 19th century China has gradually integrated occidental aesthetics in many areas and aspects and slowly internationalized its clothing patterns. This essay aims to present fashion history through its recent development in China, by giving importance to the place of its cultural and aesthetic evolution. It will summarize the Chinese fashion history into four representative turning points as follows:

Firstly, it will describe the beginnings of the “Hongxiang Fashion Corporation”, which at the beginning of the 20th century became the first Chinese clothing company to identify itself with “Fashion”, including the word shizhuang (时装) in its name, and boldly demonstrating to the Chinese people what the Western concept of “fashion” looked like. It began to introduce some occidental clothing patterns and commercial concepts, producing both purely Western clothing as well as Chinese clothing with Western influence.

Secondly, it will deal in detail with the qipao (also known as cheongsam in Cantonese), a remarkable example of East-West fusion in the history of Chinese clothing. The qipao has been popularized in the West since 2000 through Wong Kar-wai’s film, In the Mood for Love, but has a significantly longer history. It is aesthetically identified by many people as a representative clothing of Chinese traditional style, communicating national identity on international occasions.

Hu Die (胡蝶) wearing a white muslin dress designed by the Hongxiang company, c.1930s. Also known by the English nickname Butterfly Wu, Hu Die was one of the most popular Chinese actresses during the 1920s and 1930s.

Thirdly, this paper gives luxury a particularly vivid “definition”, in sight of the younger generation in China who were born since the 1980s. This generation insists more strongly on choosing luxury products of their own preference and buying clothes according to their personal taste. In general, they prefer the fashion of a bourgeois lifestyle, try to catch up with the latest Western trends, love to kill time in cafés and bars, and have become used to traveling around the world since their adolescence. Meanwhile, it is in this same period that luxury Western brands seduced the Chinese through their refined craftsmanship and concept of luxury, enabling a means for people to feel rich and appear upper class—in replacement of Chinese traditional taste, which was unfortunately forgotten for some decades.

Fourthly, the essay will chart the emergence of a Pan-Chinese style of fashion over the past five years, which has revived Chinese traditional culture as its aesthetic basis, and adapted these traditions to the taste of this younger generation. The most popular trend in Pan-Chinese style is the so-called guochao (国潮), which can be paraphrased as “China Cool”.

For Ying Xiang, this essay has been serialized into two parts. The first part, published below, groups chapters one and two to travel through the origins and history of the aesthetic fusion of East and West in Chinese clothing. The second part, chapters three and four, will concentrate on new trends and approaches to East-West fusion in the present.

1. TSUI Christine, China Fashion—Conversations with Designers, Oxford, New York: Berg, 2010, p.10.

2. LUO Gongqi, “The tailors in Pudong”, Xinmin Evening News, 26, February 2010.

The first Chinese person who mastered the technique of Western tailoring and made a first batch of women’s wear in the Western style in China was named Zhao Chunlan (赵春兰). His documents have been preserved in the Shanghai Municipal Archive Center, and he is considered as the “Father of Chinese Fashion.” Born into a tailor’s family at the beginning of the 19th century in Shanghai, Zhao joined a boys’ choir in a church in that metropolitan city. In 1848, on the choir’s tour of America1 (another document refers to England2) with a priest, Zhao began to learn the foreign tailor’s skills, and more precisely how to make Western clothes for female clients. When he returned to China, he shared his cutting and sewing knowledge with his Chinese students.

At this same time, the development of fashion and influence of Western lifestyles had already just begun to change the daily appearance of Chinese youngsters, because of the fancy clothing of the Hollywood stars and images from the European fashion magazines. This greatly stimulated the evolution of native Chinese tailors. First were the Benbang (本帮, a synonym for Shanghai style—the word “ben” means local), before some of the Benbang tailors, using many more Western ways of tailoring, developed into Hongbang (红帮, the word “hong” signified red, the color of some Western people’s hair, as distinguished from the black hair of Chinese; Hongbang thus attested to these tailors’ strong preference for the Western style). Through gradually adapting the essentials of Western tailoring techniques to traditional Chinese tailoring, the Hongbang tailors started to pay more attention to the silhouette of women’s wear, which was much more different than men’s wear. In fact, traditional Chinese tailoring is almost flat with no modeling volume, particularly from the Song Dynasty until the end of the Qing Dynasty, with no difference in silhouette between men’s wear and women’s wear as far as tailoring techniques were concerned.

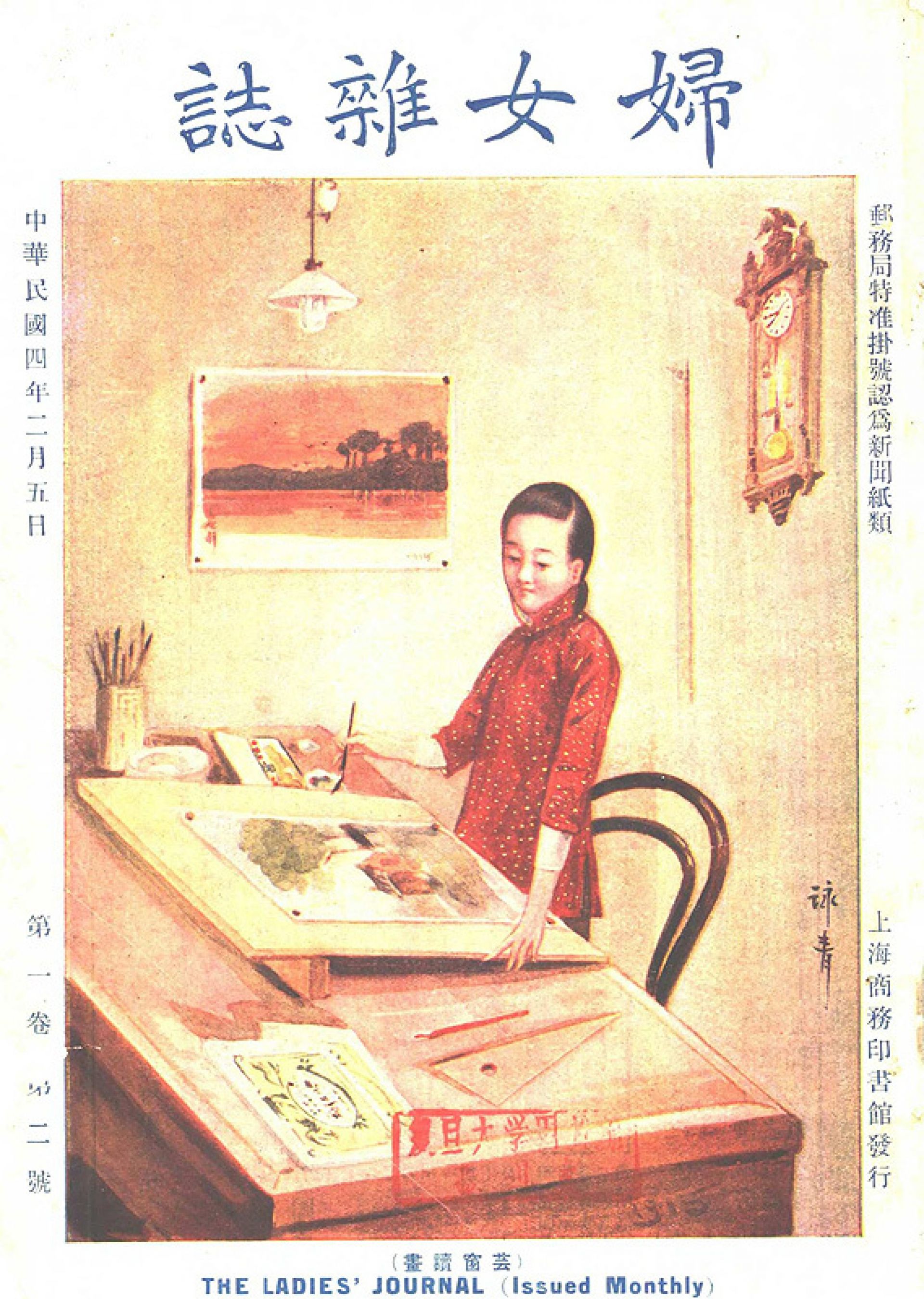

Front cover of The Ladies’ Journal (芸窗讀畫), February 1915 (painting by Xu Yongqing (徐詠青))—one of the new journals created shortly before and after the 1911 Republican revolution to satisfy and profit from public demand for reading matter on modern subjects.

An advertisement promoting the products of Nanyang Brothers Tobacco, 1931.

3. XU Hualong, The Historical Culture of Clothes in Shanghai (上海服装文化史 (Shanghai fuzhuang wenhuashi)), Shanghai: Oriental Publishing Center, 2010, p.248.

Among the Chinese Hongbang tailors were two brothers named Jin Hongxiang (金鸿翔) and Jin Yixiang (金仪翔), from the fourth generation of Zhao Chunlan’s family tree. Founded in 1917 in Shanghai, Hongxiang Fashion Corporation (鸿翔时装公司), was the first company that clearly evoked the name and meaning of “fashion” in China3. An intellectual friend of the founders’ devised the company’s name, combining the two Chinese characters shi and zhuang, respectively meaning fashion and clothes, to connote fashionable dress. Shizhuang would subsequently become a default expression for fashion and fashionable dress in the future. The Hongxiang Fashion Corporation had significant influence and impact in China, and perfectly illustrates the nature of a Chinese fashion company in that particular period—before 1949, when with the founding of the People’s Republic of China, private companies were required to close.

4. XI Zhen, The Boss in Shanghai (上海老板 (Shanghai laoban)), Shanghai: Wenhui Publishing House, 2010, p.298.

The two brothers were extremely good at promoting and selling their products to the stars, actors and celebrities of the time, who indeed looked great in their dresses. For big events, like a film festival or a celebrity’s birthday party, the designers would give their dresses free as gifts to the celebrities, in order to demonstrate their clothing. For example, a white muslin dress, a gift of the Hongxiang company, was worn by the famous film actress Hu Die (胡蝶) when she was honored as the first Queen of Chinese Cinema in 1933. Two years later, a dress was embroidered with a hundred butterflies and presented to her as a gift at her marriage, the designer inspired by the pronunciation of her name being a homophonic of butterfly (蝴蝶, Hu Die). The reputation of the Hongxiang company as a clothing brand was also built through its self-organized fashion shows of updated collections. The 1934 collection was greatly benefited by the great celebrity Hu Die, and the beautiful butterfly dress that was made for her in particular.

At the international level, it was also the Hongxiang company that designed and made a red cape of traditional Chinese style in 1947 for the marriage of Queen Elizabeth. This magnificent cape of pure silk was embroidered with a refined giant phoenix in gold and silver thread, a symbolic representation of a queen in Chinese traditional culture.4 A black lacquer box was used to contain this cape and sent to London through the British counselor in Shanghai. In return, the Hongxiang company received a letter of acknowledgement with the signature of Queen Elizabeth, and the seal of Buckingham Palace. A copy of Queen Elizabeth’s marriage cape and her autographed letter are exhibited in a glass case in the Shanghai Municipal Archive Center today.

5. The traditional moral custom for Chinese women in the Confucian principle. The Three Obediences refer to: obeying her father before her marriage, her husband when married, and her sons in widowhood; The Four Virtues refer to: traditional morality, adequate speech, dignified appearance and hard work. Together these demonstrate the spiritual restraints of submission and conjugal virtue that were imposed on women in feudal society in ancient China.

In general, the dresses made by the Hongxiang company were considered luxurious clothing, because of their much higher prices compared to other brands. With models parading around their shops in the current season’s clothes, and fashion shows held in stores on a regular basis, the company displayed itself much like the well-known “Maisons de Coutures” in Paris, such as Worth and Chanel.

The Western aesthetic went on to gradually be expressed in the appearance of Chinese dress throughout the twentieth century. Western cutting skills and three-dimensional tailoring techniques gave dresses a more feminine silhouette—highlighting the chest, waist and hips, and creating a curvier profile. In contrast, the appearance and aesthetic principles of a traditional Chinese sense of beauty were considered more reserved, discreet and subtle. The flat cutting and sewing skills of traditional Chinese tailors were able, and intended, to conceal the whole body well, especially the lines and curves of the Chinese woman, while the Chinese sense of beauty remained subject to the moral codes of the Old Empire, which told women that whatever they had to do must be done according to the "Three Obediences and Four Virtues" (三从四德)5. Moreover, as it was considered preferable that a beautiful lady followed the rules and rarely showed herself in public, the long garment that she would wear was accordingly designed to totally cover her body and hamper her walking. This same concept and shape were shared by the original qipao. Women were restricted not only through foot-binding, but also from the long-standing ritual bondage of the Empire, which was reflected in the body’s concealment and restraint by clothing.

6. DIKOTTER Frank, Things Modern: Material Culture and Everyday Life in China, London: Hurst & Company, 2007, p.73.

7. Ibid, p.107.

Obviously, the qipao represents to western gaze a national image of Chinese femininity, a piece of clothing that offers a natural bridge between the seductive romanticism and refined delicacy of "Old Shanghai" and the softness and silkiness of the style of Jiangnan (the southern region by the Yangtze River), despite this totally ignoring the fact that the qipao was actually "born" in the capital of the Old Empire: Beijing.

In fact, the qipao reflects the progress of feminine aesthetics in China throughout the twentieth century, recognizing changes in Chinese women’s national and gender identities. The original form of the qipao was quite loosely shaped and flatly cut, significantly different, if not opposite, to the way Western tailoring’s three-dimensional cutting skills seek to highlight the curves of a women’s body. In the early 20th century, a revolution in transportation followed new discoveries in Europe, beginning with the steamer in the 1860s and culminating in the advent of aviation in the 1930s.6 In China, the general movement of goods and people gradually shifted from water to wheel. New distribution points were built for foreign goods, more resources were opened up, and a denser network was shaped that extended to places far beyond China.7 These foreign goods brought convenience and beauty into daily life, as well as bearing the intangible aesthetics of the West. All the hustle and bustle of the urban landscape resulting from this revolution in transportation, combined with the import of foreign cultures, aroused people's awareness of the female beauty hidden under the loose full-length robe.

In this illustration by Yuan Xiutang, a girl poses in a lengthy qipao with Shanghai’s urban horizon in the background, during qipao’s golden era, c.1930s. (Collection of the Shanghai History Museum)

In 1912, official formal dress codes established the "embroidered blouse and pleated skirt" as the "female ceremonial costume." At the same time, women’s dresses had already started to abandon their lengthiness and a heaviness of decorative elements in favor of a shortening, narrowing and visual simplification of costume. During the revolutionary period, at the beginning of the Republic of China, costumes became increasingly tight, and women’s clothes alternated between having a "collar in the shape of silver bullion", (losing all balance and/or symmetry), and a "sleeve in the form of a trumpet", (exhibiting the wrist and a large part of the forearm). One of the significant appeals and influences of Western clothing was its ability to simplify movement: collars lost height before disappearing, changing shape from round to square, then from square to pointed. If this period of political instability between the late Qing Dynasty and the early Republic of China deprived the Chinese people of ways to improve their overall living conditions, they could at least do something for their bodies and clothes. The relative failure of the Chinese in some sectors of activity led them to move their creativity to the field of clothing.

During the twentieth century Chinese women began to accept Western culture, and pursue equality with men. But this ideal lagged behind a reality marked by significant gender inequality, a situation that maintained a sense of shame and anger among women. The first step was finally taken in the 1920s however, when cultural magazines and newspaper supplements became interested in fashion and openly created sections on costumes from around the world. The article "Evolution of Women’s Wear," published in 1921 in Shanghai’s famous Women’s Magazine (妇女杂志), critiques the fact that traditional Chinese female costume was cut too straight and covered up female beauty, advocating instead for clothing that highlighted the curves of the woman, as with the modern qipao.

8. The Chinese name of two-piece form for women is 上衣下裳 (shangyi xiachang).

9. YUAN Ze, HU Yue , Centennial Clothes (百年衣裳 (Bainian Yishang)), Beijing: JDX Joint Publishing Company, 2010, p.123

The most current explanation of women’s choice to wear the qipao at the time of the Republic of China (1912-1949) places the adoption of the dress in relation to an awareness and pursuit of women's rights. Since men wore a one-piece gown in the traditional clothing convention, women pursuing equality and progress also chose to wear a gown instead of a two-piece form (a traditional jacket/shirt and skirt)8, as if the gown was a symbol of equal significance and rights to men. Some even believe that the earliest qipao for women in the Republic of China was a men's gown, or a modified feminized form of the men's gown.9

In the late 1920s, the qipao began to change its shape significantly under Western influence—becoming tighter and fitting closer to the body, with the trumpet-shaped sleeves made shorter and narrower. From a purely academic point of view, the modern qipao found its roots in the qipao of the 1920s. In April 1929, the Nanking government implemented a new dress code that confirmed the qipao as acceptable female ceremonial dress, for an occasion paying a last, posthumous, tribute to Sun Yat-sen, who founded the Chinese Republic in 1912. The qipao was thus formalized as national costume.

It was during the 1930s that the trend of qipao reached its peak. The structure of the qipao was constantly evolving with time, its ornaments and decorative items tended towards simplification, and its length and width changed every year. Major modifications included the length of the dress’ hemline, the height of its neckline, the number of buttons on the shoulder and the length and place of its side split.

To understand the evolution of qipao, it would be appropriate to summarize the main innovations of the qipao over ten years. In 1928, the length was moderate, and the cuff of its sleeves large. In 1929, the length of the dress raised from the ankle to beneath the knees, and the sleeves were shortened. In 1930, the length of the dress was adjusted to knee height, the waist tightened, and the lap cinched like a tulip skirt. In 1931, the short qipao was a trend, tight all over and adjusted to the body, strongly exposing a woman's curves. From 1932, the dress tended to become longer again in the hemline, dropping to the ankle or lower calf. At that time, high-heeled shoes were essential for wearers of the qipao to best reveal the decorated border of the dress and to reinforce its feminine charm.

From 1933, the qipao developed its high side slits, which had previously been low or non-existent. In 1934, the wearer’s feminine curves could now be fully expressed: the high collar which had before reached up to the ears was finally shortened, and even collarless qipaos began to emerge. In 1935, the qipao dropped the length of its lower hem again, extending to the ground to meet the needs of socialites.

However, the qipao of this mid-1930s period, also called the "broom qipao," quickly saw its imposing length abandoned, transforming itself into a shorter and more practical version. Meanwhile, the Sino-Japanese war began, and the qipao changed to a length more suitable and practical for activities. In 1936, the qipao became more tailored to the body, the side split extended to above the knee, the sleeves stopped at the shoulder and the collar narrowed but remained straight. From 1937, sleeve length was shortened to about two inches below the shoulder, nearing a sleeveless shape. In 1938, the sleeves totally disappeared, and the length became shorter too, compared to the previous year.

The strong influence of Western culture in the first half of the twentieth century came to an abrupt halt for approximately 30 years following the 1966 outbreak of the Cultural Revolution. The Cultural Revolution saw the Chinese establish a very formal and utilitarian national dress code within its image of social clothing; the military costume, working costume, the Mao suit, with little variation in color between gray, green or blue. People dressed as a soldier, a farmer or a worker, as these were the most respectable professions at that time. Thus, personal appearances were closely attached to these three occupations. Occupational uniforms became everyone’s favorite clothes and were highly commended everywhere.

The aesthetics of everyday life were transformed when traditional Chinese classical culture—marked by the influence of Taoism and Confucianism—became obsolete during the Cultural Revolution. In the revolutionary period everything about classical culture had to be fought against. The Chinese people began to ignore their "traditional" and authentic concepts of beauty, and even made them disappear. On top of this, a kaleidoscope of foreign appearances eventually began to peek through the door once more. Since the economic reform of 1978 the Chinese again accepted foreign and modern things—first with curiosity, then by absorbing this European culture directly and unreservedly, consolidating their abandonment of their own culture during the Cultural Revolution. However, the image of the qipao as a symbol of the national beauty of Chinese women, and a combination of Chinese and Western culture, remained across history and in people’s hearts.

* This essay is an updated translation of a text entitled “Entre Occident et Orient: La nouvelle culture de la mode en Chine” in Esthétiques du quotidien en Chine, Paris: IFM/Regard, 2016, p.111-125. The essay’s second installment will be published in Ying Xiang’s next volume.