№1 Gaze at the Other, Gaze of the Other

Reputation Meets Opportunity

01.01.2021,

Dr Qiumei Yu is Director of Internationalization at the University for the Creative Arts (UCA) in Farnham, UK, where she is responsible for the development, implementation, and delivery of the university’s internationalization strategy. In this role, and having been based in the UK for more than ten years, she has been a privileged observer of China-UK relations with regards to creative universities and industries. The Covid-19 pandemic has put a strain on the mobility of fashion and design students from China, and East Asia in general, amongst whom the reputation and learning experience offered by UK higher education is extremely popular. The current situation offers an opportune moment to retrace and contextualize how UK creative universities have become prized tokens of international education in China, reflecting changing socioeconomic realities.

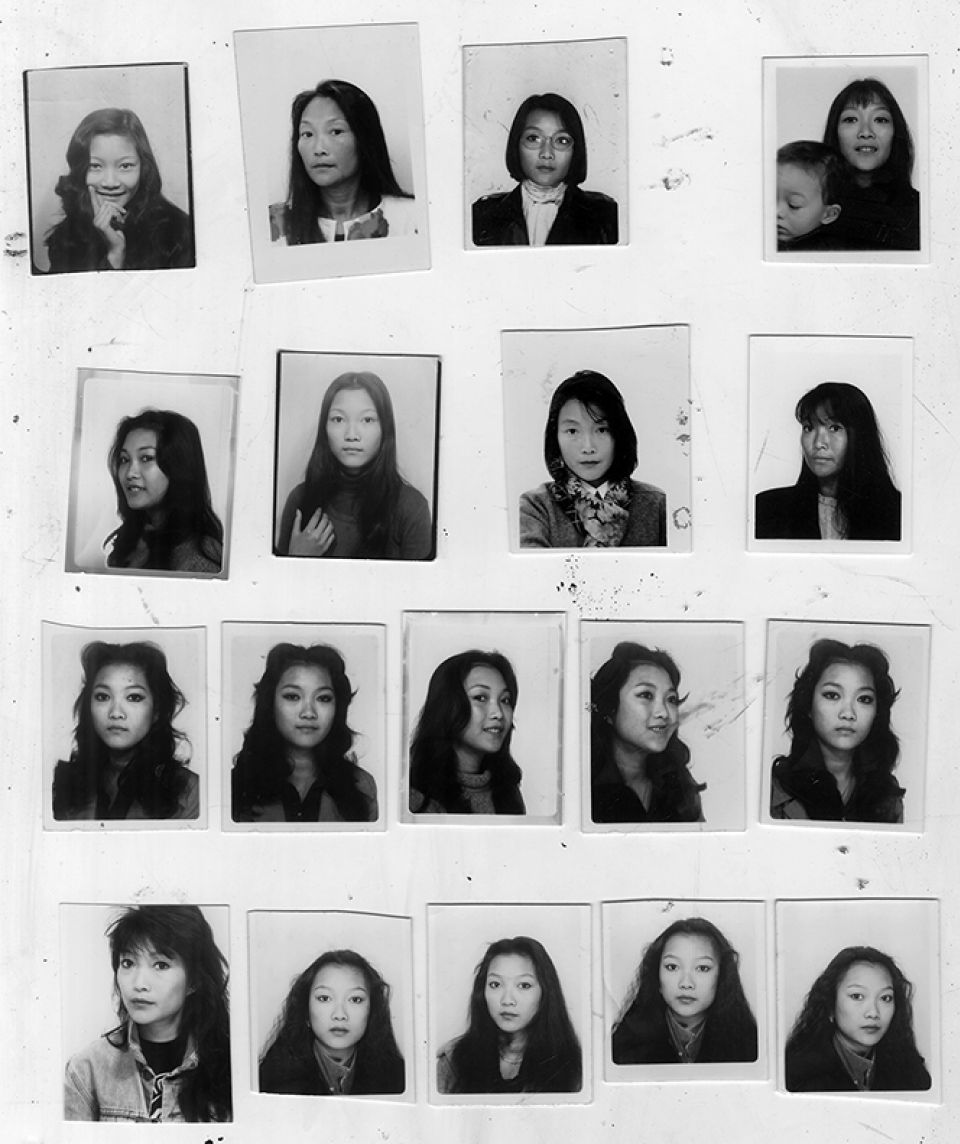

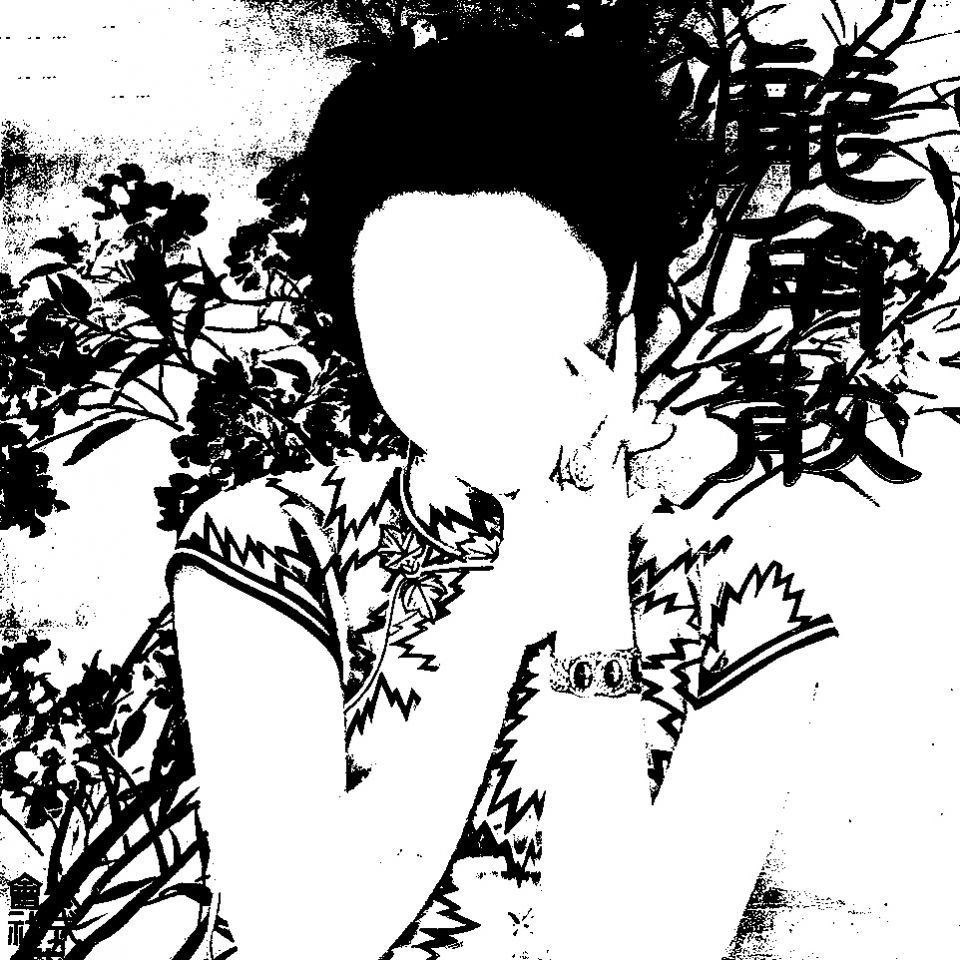

Illustration by Jiaa Li 李嘉

Adeena Mey (AM), Cheryl Qiumei Yu 喻秋梅 (QY)

AM

Can you tell us about your background and your work developing programs between China and the UK?

QY

Since completing my first degree ten years ago in China, where I am from, I have worked in the field of UK higher education. I received my MPhil from the University of Southampton and finished my PhD at Birmingham City University, where I used to work. My research is mostly around creative higher education and student mobility. I am the Director of International Studies at the University for the Creative Arts, Farnham, which involves international student recruitment and collaborations, as well as on-campus support for international students.

I have been involved in a number of collaborative programs mostly around creative disciplines—fashion, graphics, interior design, digital media, visual communication—with approximately 50 universities in China such as Xiamen University, Wuhan Textile University and Dalian Polytechnic University, centered on two models transnational education, where the UK degree is fully or partially fulfilled in China; and progression agreement, where half of the UK degree is completed in China.

Prior to my current role, that I’ve held for three years and in which I also supervise PhD students, I was Assistant Dean for Academics and ran UCA’s overseas campus in China with 1000 students in graphic design, digital media, and interior architecture.

AM

Did these roles exist before you took them on?

QY

My current role is interesting because the university had not done much international work previously. It was only four years ago, after the new Vice Chancellor joined and initiated internationalization strategies for the university, that my position and the whole department were created.

Chinese students are perceived as working really hard and good at technical skills, but scared of different ideas, or afraid of making mistakes, or to ask questions.

—Dr Cheryl Qiumei Yu 喻秋梅

AM

How have China-UK relations developed over the last couple of years, especially with regards to fashion and design?

QY

In terms of higher education, the communication is much better. China has been quite open to collaborations with the UK so that UK degrees are fully run in China, and Chinese students are encouraged to go abroad. The Ministry of Education is really encouraging. The Chinese government also set up initiatives to support staff exchange. Every year thousands of staff travel to see how teaching is done in the UK, be visiting scholars, or further their study.

This relates to the economy. Even though there has been a slow-down lately it is getting better, and more people can afford to study in the UK. In big cities in China there are large fashion events that provide a platform for idea exchange.

AM

I work at Central Saint Martins where Chinese fashion students represent a significant part of the student body and are thus important economically for the university. Did you witness this development through your work?

QY

When I was an undergraduate student in China, there were thirty students in my class. It was a very good university and only one or two studied abroad, and one went to Japan. Now, around 10% do their master's degree abroad. Ten years ago, fewer students chose to do creative subjects. However, following the Chinese government’s initiative and investment in promoting the cultural and creative industries, we have witnessed a massive boom in the creative disciplines.

AM

How are Chinese students studying fashion perceived within UK higher education?

QY

The way creative disciplines are taught in China is similar to other humanities subjects, with students copying the teacher who makes sure their concepts are correct, teaching one skill at a time. The skills and knowledge are generally quite segmented. The students are not taught the whole process of creating something – producing a garment, for instance. Students learn, step by step, but maybe when they reach the end, they might have forgotten the first step. There is limited encouragement to be different.

In China, they are scared to be different, afraid of making mistakes, and in the UK they encourage people to be different. China focuses on outcome, whereas in the UK process is just as important, for instance, in the making of a beautiful garment.

QY

Their perception of UK education is that it is shorter. A BA in China takes four years, and postgraduate studies take two/three years, which in the UK can be one year. However, the UK is very well known for the creative industries, those brands and designers, which is why students all want to come to the UK for exposure to different ideas. As a professional, I can see students need to develop their technical skills, but they also need to generate ideas and try to be different. In China, they are scared to be different, afraid of making mistakes, and in the UK they encourage people to be different. China focuses on outcome, whereas in the UK process is just as important, for instance, in the making of a beautiful garment.

AM

How does this different way of learning and teaching challenge Chinese students? As a result, how are Chinese students perceived within the creative industries in the UK?

QY

In general, Chinese students are perceived as working really hard and good at technical skills, but scared of different ideas, or afraid of making mistakes, or to ask questions.

AM

Why would a Chinese student choose the UK, instead of France or the US?

QY

In terms of fashion, a lot of Chinese students want to go to the US for its top design schools, which is similar to the UK. The attraction to the UK is to its heritage, while the US is sought after for being more open minded. Much fewer students go to France, even though they don't charge international student fees, also due to the language barrier. The UK has been very proactive in promoting its brand, contributing to the universities’ budgets. By waiving international student tuition fees, France also promotes its brand, but they are less active.

AM

Would you say this is because the French system relies less on international money,

whereas in the UK the financial question is huge?

QY

Yes.

AM

A lot of students from China would choose to study due to a country’s reputation, but the UK has built that reputation on economic grounds mostly.

QY

It is also an issue of language because in China we all have to study English, not French.

AM

Obviously the pandemic has had an impact, limiting how many students can come to the UK to study.

QY

Most of the current generation are from the one child policy period, which means the parents don’t want their only child to take any risks. The pandemic is much worse in Europe than China. Also, generally students who study creative disciplines are from relatively wealthy families. They need to handle extracurricular courses, and tuition is higher. Health and safety is a priority for Chinese parents.

We all know students in creative disciplines need to have access to workshops. So, there has been quite a big impact on the Chinese students coming to the UK, which I think is about a 30–50% decrease in enrollment, and a 10–20% decrease in applications.

Most of the current generation are from the one child policy period, which means the parents don’t want their only child to take any risks.

AM

Have you also seen that decline in enrollment in China?

QY

In China there is a decrease, but it is relatively small. However, even with the pandemic we attract students from South Asia, India, and Bangladesh. Because of the new UK government’s policy on graduate routes, after they graduate they can work in the UK for two years. So, this has created a new trend.

AM

How do you think the role and perception of Chinese students in the UK will evolve in the coming years?

QY

I feel very optimistic that the UK will be more welcoming toward Chinese students. Unlike the South Asian students who go to China and want to stay, Chinese students just want to go to the UK to study and then return home to pursue their careers. The economy is getting better in China, and more students are able to speak better English, even than five years ago, which will help with integration in the UK and make them comfortable and feel they are part of the community. Nowadays, they are more individualist, so they are more confident in presenting their own opinions and ideas.

AM

Do you think that this change might encourage Chinese students to stay in the UK?

QY

The majority will want to go back to China where there are more opportunities.

AM

What changes have you seen as a result of an increasing number of Chinese students having studied fashion or design in the UK—in the scene but also on an institutional level, or in the curriculum given the exchange between British and Chinese universities, that might see students stay in China rather than go abroad?

QY

Recently Chinese governments have expanded the postgraduate provisions in China to encourage more students to stay. However, most students or families aren’t able to afford to study abroad, and just want to have a different experience. The Chinese government wants to keep students in China, but it is unlikely to reduce the number who want to go abroad.

DR QIUMEI CHERYL YU 喻秋梅

Cheryl is Director of Internationalisation at UCA, where she previously established and led the department of International Studies. Her research focuses on a comparative study of art and design higher education between China and the UK, as well as international students’ mobility and TNE (transnational education).

ADEENA MEY

is a researcher, curator and lecturer. He is Associate Editor of Ying Xiang and Managing Editor of Afterall Journal, based at Central St Martins, University of the Arts London, where he leads the research project The Black Atlantic Museum. He is also co-director of the book series Cinétisme at Les Presses du réel.

JIAA LI 李嘉

is an illustrator based in Shanghai, focused on the fragmentation of words and imagery she has faced in real life. Her protocol is to collect the seemingly obvious things, and to recreate them in her own visual languages.

related content

Staging the Orient

—

Professor Homay King discusses the social implications of Orientalism in cinema, the cultural construction of an East Asian imaginary, and present day negotiations of representation.

Clothing as Vessel

—

Artist Bruno Zhu talks shop, reflecting on a year of personal revelations in 2020, navigating identity, clothing as a vessel for failure, and essential/nonessential languages.

A Letter from a Voyager

—

A letter from the editor describing her journey to Ying Xiang.