№1 Gaze at the Other, Gaze of the Other

A “Vaguely Asian” Clothing Enterprise

30.05.2021,

The term “vaguely Asian” frequently pops up, as a characterization experiences of race and estrangement that allows for cultural dissonances. Designs from their Bushwick studio are hand crafted further afield in East and Southeast Asia, and with these CFGNY are weaving new threads of solidarity to clothe a growing web of collaborators. Their most recent collection addresses asymmetries in representation and access as revealed by COVID-19, but with far deeper structural roots. Garments as sculptural form are on view alongside a number of interventions but various artist-collaborators at Auto Italia in London.

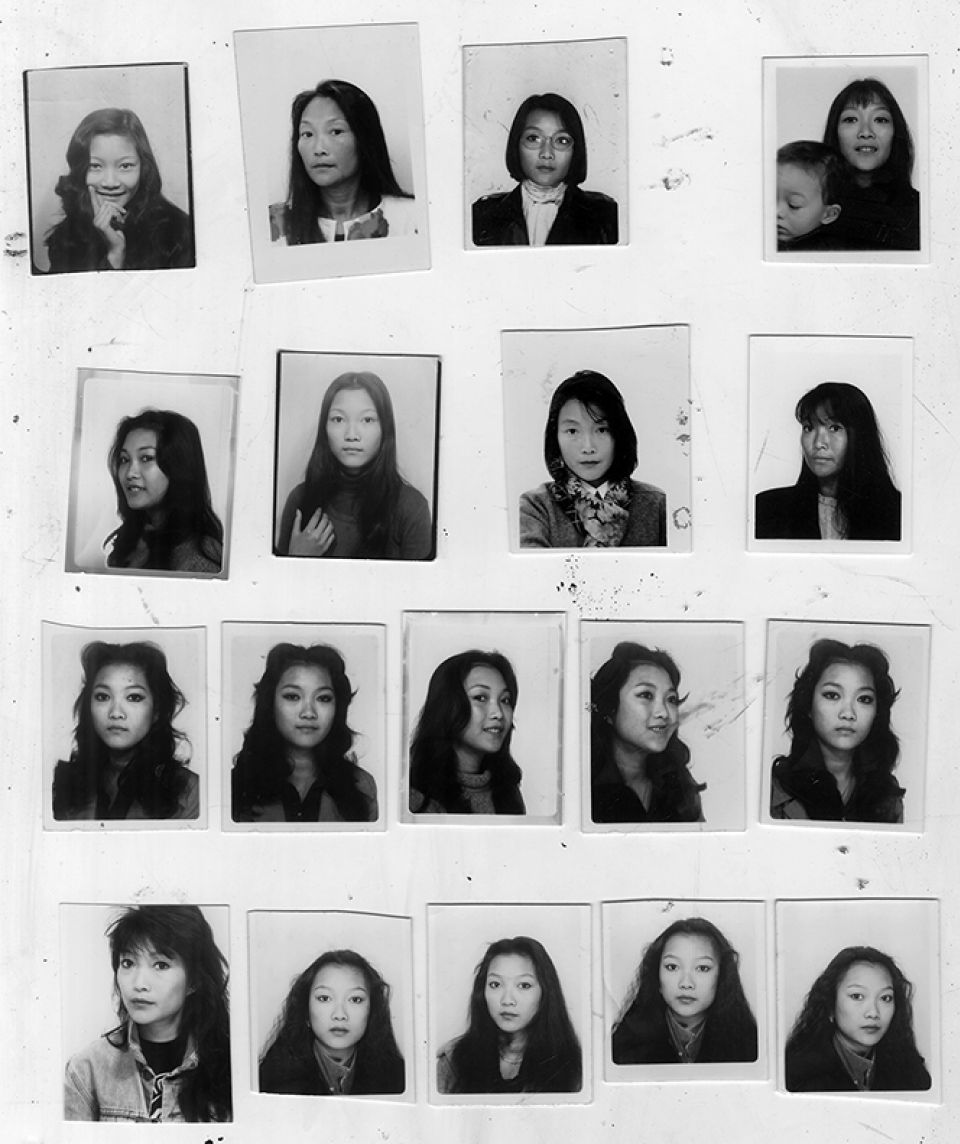

Photo: Mary Kang

Daniel Chew (DC), Tin Nguyen (TN) and Ming Lin (ML)

DC

In Chinatown, when I first got here in 2006, I would often be mistaken for being Japanese. But now this idea of “speaks the streets” style being from Japan is outmoded. If you go on Instagram, it’s all about Chinese street style, and it’s very much connected to entering into this luxury market. It’s basically a class thing.

ML

Was there a certain pride in being mis-identified as a Japanese person?

DC

Sort of, it was just that Chinese wasn’t thought of as being fashionable, in 2006. You were just defaulted to Japanese if you were Asian and had style. Because that was thought of as where street fashion came from.

ML

Which may also be because of the fact that Japan was the most open, the most Westernized of East Asian countries.

DC

Right. Economically as well. They modernized to become a Western-style economy in the early 1900s.

But it’s interesting because the new street fashion that you see on Instagram, it’s all from people in China, all about how sick the fashion from China is. You’ve seen those TikToks right?

TN

And maybe it’s also that it’s TikTok that’s circulating the information. TikTok is from China. It’s fashion, but it’s also media.

DC

It’s basically the increasing dominance of China within the globalized world.

TN

It’s not like the clothes that they are wearing in China are very different…

DC

No, they’re the same.

Photo: Sarah Chow

Chinese wasn’t thought of as being fashionable, in 2006. You were just defaulted to Japanese if you were Asian and had style. Because that was thought of as where street fashion came from.

—Daniel Chew

Photos credit: Mary Kang

ML

I’m always interested in how Chinese diaspora in the US have inhabited these different subcultures that didn’t necessarily come from their own traditions in order to assimilate—whether Japanese anime culture, or hip hop culture. What I witness in the CFGNY project has something to do with breaking down these terms of appropriation and laying them bare, both in the aesthetic of the clothes, but also in the mode of production. There’s also an element of exchange, or acknowledgment of the two-way transmission—between self and other, metropole and periphery, producer and consumer. What I want to speak to you about today is how the method of production forms the meaning of the work. But maybe we can start with something basic like, how did you start working collectively?

TN

Daniel and I met in the art scene. At that time I guess there was still an element of, like, when you’re hanging out in a group you notice other Asians. We became friends.

DC

OK, so growing up Asian in America, you are more socialized to become part of a white world, versus like a Latino or black world. It’s a split that happens.

TN

It depends on where you are from.

DC

We grew up in that. It’s a class thing. There are of course Asians that grow up in different cultures, but for us, and a lot of the people around us, if you were Asian and you were hanging out with someone that wasn’t Asian, you were most likely incorporated into a sort of white space. This partakes in this sort of model minority myth, a problematic idea, but that’s what we were existing in—in this white art world where, at that time, we didn’t really talk about race.

ML

What year did you meet?

DC

2010. So this wasn’t even that long ago. What happened was that we obviously noticed each other because we’re gay and Asian in this white scene. I think that one thing that you internalize, or at least I did, is that you get competitive with this other person, because you’re used to being special.

TN

Because you’re also tokenized within the wider circle.

DC

I think instead of being competitive with one another, we made the deliberate decision to be friends. But then we actually became friends. I think we were both within ourselves going through these questions, and then we were able to be in dialogue with each other. It was like, why should we be competitive with each other when we should be collaborating with each other?

TN

We were never really that competitive with one another. But we saw other peers in the same situation of being Asian and feeling competition with one another.

DC

I definitely recognized that impulse within myself too.

TN

Yeah, for sure.

DC

So that’s how we became friends and started this dialogue. And also at the same time we were buying a lot of clothes.

I was already into fashion in high school. I was on a lot of forums. I loved fashion always. We both loved shopping. We’d go to these sample sales and joke, like “we’re cheap and Asian.” We’d say shit like that while standing in line at the sample sale for two hours…

So this is where we developed this feeling, or notion of Asianness, that isn’t really Asian, that connects us.

Photos credit: Studio Phong (Cao Trí Củ)

ML

Vaguely Asian?

DC

It’s vaguely Asian, exactly.

TN

Getting things cheap and loving deals.

And at the sample sales, that’s where we would also see all of the other queer Asians. And they later became the models that we cast…

DC

Yes, but later. So basically we were at the sample sale, talking about being cheap, and then Tin was like, I wanna spend more time in Vietnam because I’ve only been there once or twice. My mom goes there to make clothes. We should just start making clothes. We could do it more like an art project. It wouldn’t need to be a production line.

TN

Also, in going to a place like Asia, because fashion or garment-making is so well understood throughout its cities, it’s a way to be able to penetrate the city—in opposition to something like art, which is so niche and not a conversation that the general public is having there. Going to Vietnam with the purpose of making clothes allows you to see more of how the inner worlds are sort of organized. And meeting people, getting invited to the tailors’ home, provides a kind of insight that was why making fashion was of interest to us in the first place.

DC

So that’s basically how we started—tailor shops, Tin’s mom. Tin went to Vietnam, and we got started.

TN

And what we’re doing is, because we are coming from a specific community, the art world, we’ve been pre-ordering to support each collection. We’ve done that for each season, which basically has allowed this to kind of work more freely without the constraints of industry.

ML

Why choose to situate it in an art context over a fashion context? Does living in this economy shift the meaning for you?

TN

I think it’s for the dialogue that this allows to happen.

DC

I think we wanted to take it to a different place, where people might actually engage with it (on an intellectual level?).

TN

The way in which art is read moves at a much slower pace. Fashion, because it has to move so quickly in relation to its industry cycle you lose all of this conversation that could be there, but can’t be because there’s this drive that doesn’t allow it.

ML

I sort of read in this project that one of the mediums is circulation itself, and playing with different models of doing this.

DC

For sure. And I think it’s also an attention to, and inhabiting of, certain fashion models, but doing something different with them.

TN

But in the same sense, there’s also a lot in the art world that we don’t participate in and instead look towards fashion. So it’s not that we are idolizing the art world specifically, it’s that we are using both sorts of networks and mending (?) them on our own terms.

ML

How do you build these networks?

TN

I think the networks continue to build upon themselves. For instance, we were friends with KK, because we worked with her at a gallery for an artist, and when we were casting we were like, do you know other Asians? And she was like yeah, of course. Then we would contact them, or have her contact them, and at that time they were kind of yearning for this dialogue as well.

DC

The idea for the first show was that we wanted to take this dialogue that Tin and I were having about this sort of diaspora identity thing and expand it by inviting people to be part of this fashion show.

Going to Vietnam with the purpose of making clothes allows you to see more of how the inner worlds are sort of organized. And meeting people, getting invited to the tailors’ home, provides a kind of insight that was why making fashion was of interest to us in the first place.

—Tin Nguyen

ML

So I have a question about the relationship between the runway shows and the sort of extra-curricular activities. I seem to recall there was a closed discussion at the Museum of Chinese in America?

DC

So how this closed discussion took place at MoCA and then at 47 was that Tin had first talked about having that closed conversation with Howie Chen. It was during the time when there was the controversy surrounding the Dana Schutz painting of Emmett Till at the Whitney, curated by Chris Lew.

TN

So it was a closed discussion, and because it was a closed discussion, and also because most people were Asian identifying, people were able to speak more freely.

DC

It was also about complicity. Because Chris is Asian, people were sort of questioning his stance on the sort of wider race conversation.

So Tin participated in the first conversation, which was also about a generational difference, about not all parties being able to understand the stakes of it. But then there were these sorts of institutional figures being like, you don’t understand what it’s like to work at an institution, this is already more than what I could have expected in my time.

Tin was very inspired by that conversation and told me about it. We thought that this was something that we wanted to continue. So we asked Howie if he wanted to facilitate another conversation under the helm of Cover Street Market, which was one of our first events where we were selling clothes to raise funds for the project. That’s how we do it, we don’t sell clothes to make money, we sell clothes to make enough money for the next part of our journey.

So we had this holiday shop at 47 Canal alongside programming, and one of the programs that we wanted to do was this second closed conversation. It was CFGNY hosting and leading the conversation.

TN

The main value of that format is that you’re able to have a conversation that you might not be able to have if it were multi-race. Whether or not that discussion led us anywhere or got us to anywhere specific, I do think that in having that kind of shared space there’s a kind of recognition that happens.

ML

I think one of the reasons that this conversation, or its lore, stuck in my mind was because it was the first time I had ever heard of Eugenia Tsai. I remember you mentioned that there was this curator at the Brooklyn Museum who was quite reticent to back up any criticisms against the Whitney’s curators of color, and finding that interesting. But it seems like she’s now a big fan of your project?

DC

Oh yeah.

TN

I think regardless of what resulted from the conversation it was this reckoning for the people involved, people who hadn’t thought of themselves as under this larger racial subject group, and who, whether they like it or not, are influenced and affected by these larger histories and power structures, and I think it was important for a lot of people to recognize that, being surrounded by people talking about that for the first time.

ML

It does seem like there is this self-effacing quality at work, where people that share characteristics or backgrounds are not necessarily compelled to band together, but rather are repelled by these markers or identifications.

TN

Yeah, there were people that we invited that didn’t show up.

DC

But I do think that a lot has already changed since we first started.

ML

I think that’s something really beautiful, that somehow you created the clothing or costume for people to don to feel more unified. The CFGNY uniform became a unifier.

Photo credit: Studio Phong (Cao Trí Củ)

Photo credit: David Brandon Geeting

ML

So now you have plans to be mass market?

DC

I don’t know if it’s mass market, but it’s more like, where do we find the time to work on this? We live in New York, we work on this a lot and don’t get paid for it. We ask our friends for too many favors. We want to be able to pay people.

TN

I think we are more aware now of what the possibilities around the brand are, how people perceive it and what people sort of desire within it, and it’s just about making decisions that connect those dots more specifically. Before there was a lot of decision-making happening within a larger sphere of ideas...

DC

Or like we were just doing what we felt like.

TN

Yeah. And I mean of course we still do that as well…

ML

It seems like that’s what having one foot in the fashion world and one foot in the art world allows you to do. You achieve a level of semi-autonomy by not being beholden to institutions or benefactors.

DC

But the pitfalls of that are that you have to figure out how to make money, basically.

TN

You don’t get the full support of either community.

DC

Which illustrates why we did the sale this year. It’s because we had all of these clothes from a year ago and we needed to try to sell them. Six months before Covid, it was all here… We do stuff like this where something is unanticipated or uncoordinated, but it’s because we have jobs, etc. We’d like to be able to structure our lives around it more.

ML

You each have three jobs: your independent practices, CFGNY, your day job…

DC & TN

Yeah.

Photo credit: Mary Kang

ML

I want to hear about your relationship with the tailors. Do you consider your tailors as collaborators?

TN

It depends. On our last project with Triple Canopy, we officially included the tailors as collaborators. We got permission from them to do so. Because in the past we have worked with them and we did see it as collaborative to some degree, and they didn’t get any credit for it—that is the nature of that type of production in fashion, it is collaborative but it’s not attributive as such. So with the Triple Canopy project specifically that was the idea, that we really present their work and their ideas, as part of a collaborative collection.

ML

How did that go? Were they receptive to that?

TN

Some tailors were like, we just cut and sew, you direct us, we don’t provide creative services. They were unwilling to do it. Whereas others were. There were these two sisters where one of them wanted to study fashion, but had to study something practical, and then ended up going back into tailoring. When she designed with us she was really excited because that is what she wants to do. So she was really able to create and be supported throughout her whole vision.

DC

And I just wanted to go back to how we came upon this idea of a collaborative process. Tin and I taught ourselves how to sew, but we don’t know how to sew that well. So we would sew a really, really shitty muslin sample that wasn’t finished at all, but just had the right cut.

TN

The silhouette.

DC

And then we’d give it to someone and they would have to make so many decisions for us on how to finish it. They had to make a lot of creative decisions for different things. Sometimes, we’d get it back and be like, ugh this is so ugly, the fold is wrong, etc. And then sometimes we’d get things back where we hadn’t asked for a certain thing, but they’d just done it. It was kind of off, but we would like how off it was. And then that becomes a sort of signature thing that we would start doing. We liked the sort of “mistranslation” of what we were trying to do but through their eyes. For the Triple Canopy project, we wanted to take that part of the process and emphasize it, and then that led to having them come on as collaborators on the project.

ML

What did they understand you as?

DC

As fashion designers.

TN

We have to label things really specifically for them to understand.

DC

It’s also because of the language barrier. Tin can speak conversational Vietnamese, but he can’t have a philosophical dialogue with them. So we have to keep things simple. So part of the Triple Canopy project was also us trying to explain to them our project. We were like, how do you interpret our project about Asian diaspora identity? But they don’t have this idea of diaspora identity inherent to them, so what became crucial was, how do we talk to them?

TN

One way we put it simply was like, he’s Chinese, I’m Vietnamese, and we hang out—so emphasizing this idea that there’s overlap (and camaraderie?) in the ways in which we, as Asian diaspora, identify. They were often surprised by that, that a Chinese and Vietnamese might identify with one another in America.

DC

Also, we’re just foreigners to them too.

ML

So you’re going to these countries, the factories of the world that are often derided for their production of a sub-par quality or standard, yet which the world relies on, and then trying to attribute them creative agency and authorship. I wonder, what does that mean to them and is that something that they even desire?

DC

I think even for the Triple Canopy thing, we were like, we’ll pay you more. We had access to this budget, and we were like, part of this would be about redistribution. We told them they could design whatever they wanted and we would pay them more than they normally would charge us.

TN

We would literally say, with every design, tell us the amount you think it’s worth. Some of them were just overwhelmed and annoyed. But we were like, we’ll give you whatever you want! I would beg them online, for months.

DC

And so I think redistribution is also an important element of what we are trying to do.

TN

I think because we’ve worked with the same people over the years there’s a lot of trust. I think overall they understand that we are here to support them. There’s a specific style that you kind of have to embody to work with them. There are some tailors where the relationship has grown, and others that we don’t work with anymore. We had to learn how to be respectful, to be understanding, and how to fulfill their requirements. So I think when we have these more collaborative projects, where we are giving them more money and giving them more authorship, I don’t think it matters more or less. I think overall it’s just this constant relationship that they are seeing with us.

DC

But I also think the collaborative thing just extends the way in which we like to work. We work collaboratively with people here, and it’s just us continuing that.

ML

I’m curious how, if you were to “professionalize” or become more mainstream, so to speak, how you would navigate or maintain that kind of radical gesture of collaboration as a sort of destabilization of the typical production hierarchy?

TN

I think what’s understood as professional is shifting—in relation to like major cities having fashion week, having magazines write about brands, selling in stores—but not with what we’re seeing. A lot of brands are starting to sell directly to the consumer, and you can be your own media outlet, and you do have the chance to professionalize within that setting. So it is this more internal discussion that you are having with your viewer, rather than this conversation mediated between fashion magazines, fashion week, etc. So in a sense I think while we are professionalizing, I don’t think it will be within that sort of old understanding of what the industry is. More so, just professionalizing in the sense that we would practice more regularly or be more in touch with our consumers or viewers and would be able to support ourselves.

CFGNY is an open acronym that might stand for “Concept Foreign Garments New York.”

ML

So what are some of the alternative models that you’re exploring?

TN

Well one thing is that, because of Covid, I’ve had this idea of doing production with the Asian diaspora within the US. Outside of Boston, there’s a city called Dorchester that I visited growing up. Recently I had my mom call her friends there and ask them to put up flyers to look for tailors. I ended up visiting three different people, and it was kind of amazing to see their setups and what they were doing. One couple used to have a tailoring company, so they had 30 industrial sewing machines. It was just this house with a garden and inside the house, the living room basically, was like a tailoring shop. So it was seeing this alternative tailor economy within the home setting.

ML

Were they working with larger brands, or?

TN

There’s a range. The couple was doing sub-contracting. They were in touch with bigger brands.

ML

Is it a higher price point than in Vietnam?

DC

It’s always about volume. Because we don’t make large amounts it’s always more expensive. But we save on shipping. And anyways, it’s part of the project.

TN

We’ll continue to produce in Vietnam as well, but we’re thinking to also start this project of producing more locally in order to have this conversation with other diaspora in the US. And again we are sampling with them, and it’s this mistranslation of the material as well. Whereas the tailors in Vietnam may not be accustomed to the styles here, these tailors live here, have children, so they have an interpretation of it. We’ll continue to experiment with the sorts of translations that result from this.

ML

Speaking of mis-translations and mis-interpretations, can you lastly tell me what CFGNY stands for?

DC

CFGNY is an open acronym that might stand for “Concept Foreign Garments New York.”

ML

What does it mean for you today?

DC

It still very much speaks to that.

TN

And then there’s the bootleg translation, “Cute Fucking Gay New York.”

This conversation took place on 10 October 2020.

CFGNY

began in 2016 as an ongoing dialogue between Tin Nguyen and Daniel Chew, joined by Kirsten Kilponen and Ten Izu in 2020, on the intersection of fashion, race, identity and sexuality.

MING LIN

is an artist, writer and researcher who lives and works in New York.

related content

A “Vaguely Asian” Clothing Enterprise

—

CFGNY (Concept Foreign Gaments New York / Cute Fucking Gay New York) is a collective fashion enterprise based out of New York City, started by artists Tin Nguyen and Daniel Chew in 2016, and later joined by Kirsten Kilponen and Ten Izu in 2020. The project weaves diasporic experience and networks of production into conceptual collections that straddle art and industry.

Staging the Orient

—

Professor Homay King discusses the social implications of Orientalism in cinema, the cultural construction of an East Asian imaginary, and present day negotiations of representation.

Clothing as Vessel

—

Artist Bruno Zhu talks shop, reflecting on a year of personal revelations in 2020, navigating identity, clothing as a vessel for failure, and essential/nonessential languages.